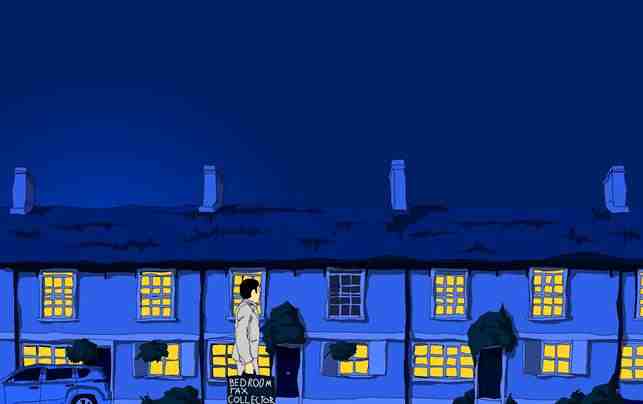

Next April housing benefit recipients under-occupying social homes will be forced to choose between paying a penalty or moving to a smaller property. Here Jules Birch examines the impact on tenants and landlords in the rural south west, where alternative homes are in short supply

Carol Solan faces a choice next April. Will she stay in the home that new housing benefit rules say she is under-occupying, cobbling together an extra £14 a week, or will she move somewhere smaller?

Ms Solan, 55, lives with her husband Eddie, 58, and daughter Tamika, 18, in a three-bedroom house in the picturesque village of Marshfield, on the edge of the Cotswolds in Gloucestershire.

Under the rules that come into effect next April, the Solans are under-occupying the home, even though ill-health means Mr Solan has to sleep in the spare room by himself.

‘We can’t move,’ says Ms Solan. ‘My husband would go mad if we moved away from the countryside. We’ve been here five years and we’ve put an awful lot of work into the house and the garden. When we got here the house was just an empty shell and the garden was full of car and motorcycle parts.’

Variations on the same story will be echoed by hundreds of thousands of other social housing tenants across the UK next year. The under-occupation penalty or ‘bedroom tax’ docks a percentage of housing benefit that rises with the number of spare bedrooms – 14 per cent for one spare room and up to 25 per cent for two. The penalty applies to housing benefit recipients of working age. It has been designed to save around £490 million and the government’s impact assessment estimates that 670,000 tenants will be affected including 30,000 in the south west.

No alternative

However, under-occupiers who live in rural communities like Marshfield know there is virtually no chance of downsizing locally. The social housing stock that has not been sold under right to buy will usually be family-sized homes or sheltered accommodation for older people. Even if smaller homes are available in the nearest town – and that’s a big if – it would mean moving miles away from friends and family and community ties. So where does this leave social landlords and their tenants?

For Ms Solan the only option will be to find the money from somewhere at a time when bills are rising and benefits are falling. Again, living in the countryside will make things tougher. ‘Being so rural we have to have a car,’ says Ms Solan. ‘The price of petrol is going up all the time. It’s the only way our daughter can get to college – and they [the government] have taken away her education maintenance allowance too.’

Ms Solan’s landlord, Merlin Housing Society, owns 31 general needs and 17 sheltered homes in Marshfield. ‘We know these changes will have a potentially large impact on many of our residents,’ says operations direction Amanda Meanwell. ‘Given that we cover both rural areas like Marshfield and the northern edge of Bristol, that impact could be very, very different.’

For rural landlords the good news is that rates of employment among their tenants tend to be higher than in more urban areas and so they are less likely to be affected by the bedroom tax. However, those who are in low-paid employment and receive housing benefit will also be subjected to it.

‘Rural affordable housing in general has a different employment profile to social housing as a whole,’ says Adrian Maunders, chief executive of 1,000-home English Rural Housing Association and chair of the National Housing Federation’s Rural Alliance. ‘More than 60 per cent of our tenants are in full-time employment.’

Although he admits that he does worry that levels of seasonal employment tend to be higher in the south west of England, in sectors like tourism.

Town and country

Richard Kitson, chair of 239-home Wiltshire Rural Housing Association, agrees. ‘There are fewer jobs around in villages but those that are in, say, agriculture and forestry tend to be for the longer term even if they are lower paid.’

The bad news is that rural associations tend to build larger homes and under-occupation tends to be higher. ‘Because we don’t build many homes in rural areas we try and make sure that what we do build is as flexible as possible,’ explains Mr Kitson. ‘That can be a problem because the people are likely to under-occupy at some stage in advance of starting a family. Building affordable family-sized homes is part of our commitment to keep youngsters, in particular, in villages where they would normally be priced out.’

‘Traditionally rural housing has been aimed at helping young families in rural communities so we needed two and three-bedroom homes. Sometimes they might have one child initially and a spare bedroom,’ adds Mr Maunders.

The problem for rural landlords is that, as Paul Smith, head of research and development at Aster Group, puts it: ‘Flexibility to meet people’s need locally is going to be much less in rural areas. People will have to choose whether to take the hit or move out of the community they are in.’ Aster has 17,000 homes across the south and south west, including Wiltshire and Somerset.

On the move

Spectrum Housing Group, which owns 18,000 homes and operates in Dorset and the Isle of Wight, is trying to find ways to prioritise people who want to move to smaller accommodation – this means talking to local authorities about changes to allocation priorities under choice-based lettings. The housing association’s neighbourhood services director Stuart Davies admits there are limits to what can be done. ‘The likelihood is that because of the right to buy and difficulties in getting development going it’s not likely you’re going to be able to downsize in villages or even in market towns.’

He cites the example of the village where he lives in Wiltshire where demand for housing is such that 100 families competed for just one social rented home that became available in the past two years.

‘Where we live the nearest town is six or seven miles away and we’re talking about people who might have been there for 20 or 30 years who will be forced to choose between a reduced income and having to move some distance away,’ he says.

Wiltshire Council believes most of the tenants who will be affected by the bedroom tax live in towns like Salisbury and Trowbridge – not rural areas. However, a spokesperson for the authority acknowledges that it faces particular difficulty because of the rural nature of the county and the dispersal of social housing in villages and hamlets.

The local authority quotes the example of the parish of Steeple Langford, which has a population of around 500 people and just 29 social rented homes. That means any family that wants to move will find it much harder to stay in their home area than people in towns.

Wiltshire Rural’s Mr Kitson worries that the bedroom tax could make things even worse in the long term. ‘It’s making us think more about building smaller properties to avoid under-occupation and that gives us less flexibility for the future,’ he says.

Assessing the impact

A spokesperson for the Department for Work and Pensions insists that ‘it is not fair or affordable for people to continue living in homes that are too large for their needs when in England alone there are around 5 million people on the social housing waiting list, and more than a quarter of a million tenants living in overcrowded conditions’.

‘We are currently working with social landlords to ensure tenants are made aware of the changes well in advance,’ they add.

The introduction of the bedroom tax is still almost a year away and social landlords across the country are working hard to get a true picture of exactly how many of their tenants will be affected: how many are on housing benefit; how many of those are under-occupying; and how many of those are of working age.

This is no simple matter even for a small landlord. Wiltshire Rural has 239 homes in 35 different villages. Its initial work with tenants suggests that 70 households (29 per cent) are under-occupying under the new rules and that another 20 might be, depending on the age and gender of their children. Some 59 per cent of tenants are employed but more than a third of those earn between £10,000 and £15,000, so could be on partial housing benefit and will therefore be affected by the bedroom tax.

Other landlords are continuing their household profiling work and planning their campaigning and communication strategy to alert tenants to the approaching changes. Merlin, for example, is working with other associations in the south west. Other landlords are beefing up their benefits advice capabilities.

However, for tenants, the bedroom tax comes on top of other cuts to housing and other benefits, reductions in tax credits and upcoming changes to the way benefits are paid.

Back in Marshfield, Ms Solan is better informed than most as she is a member of Merlin’s residents inspecting services team, and also a former tenant board member. As a regular reader of Inside Housing she followed the debate around the Welfare Reform Bill which heralded the cuts to benefits and the way they are paid.

‘I just think they’re hurting the least advantaged people in the community,’ she says of the government. ‘If someone is living in a three-bedroom house because of health reasons and they are looking after the property, then leave them alone. They are just not looking at individual cases.’

Room to spare: the impact of the bedroom tax in the south west

The equality impact assessment of the under-occupation penalty, published by the Department for Work and Pensions in October 2011, estimates that 30,000 households will be affected in England’s south west – that’s 28 per cent of working age housing benefit claimants who will lose an average of £13 a week.

The assessment also admitted that there would be specific impacts in rural areas with lower concentrations of social housing. ‘This could result in: the restriction being applied to the claimant’s rent even though there is little suitable accommodation available in the area; the tenant considering moving further distances in order to secure accommodation of the appropriate size; in some cases the tenant could consider moving into the private rented sector; or rent out a room.’

The bedroom tax will be followed by radical changes in the whole benefits system. Introduction of the universal credit starts from October 2013 and direct payment of housing benefit to tenants is set to be part of the new system.

Andy Tate, policy officer at the National Housing Federation, says there could be a rural dimension to both. ‘If you need to deal with the whole payment yourself that’s an issue for people who don’t have a bank account and in rural areas where the bank is miles away – what if you don’t have a car and there is only one bus in the morning? The DWP is expecting 80 per cent of claims for universal credit to be made online. What if there is no broadband in a rural area?’

An implication of the Bedroom Tax is that two adults who identify as a couple will share a bedroom. That”s a massive assumption. In the case above, the woman has her own bedroom, and I suspect that is reasonably common. Among people who have grown apart but want to continue to share a home, or who no longer have a relationship but for practical or financial reasons continue to share a home, or simply where the partners want a bit of space and independence.