Years of evidence exposes minister’s claims in parliament that DWP is not to blame for deaths

Years of evidence shows clearly how a “violent” culture that developed within the Department for Work and Pensions over three decades was responsible for countless deaths of disabled benefit claimants, despite a minister’s claims last week in parliament.

The evidence has been brought together by Disability News Service (DNS) to respond to claims by Sir Stephen Timms, the minister for social security and disability, that the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) was not responsible for the harm and deaths caused to thousands of disabled people.

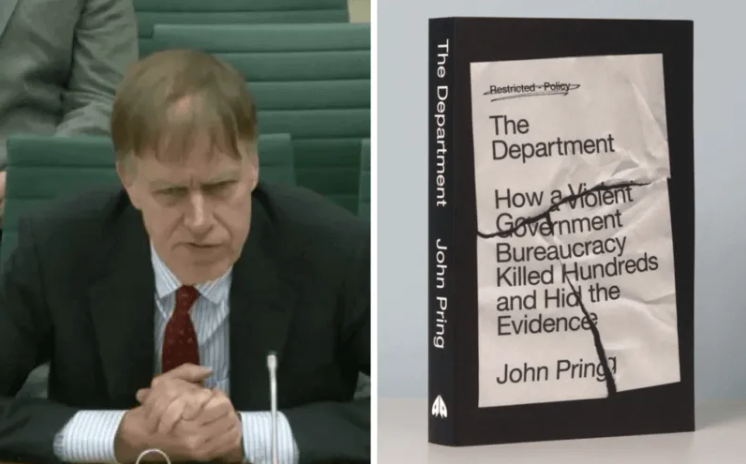

Sir Stephen had delayed the end of last week’s Commons work and pensions committee evidence session to deliver a statement about The Department, a book written by DNS editor John Pring which exposes the “violent government bureaucracy” within DWP that has led to hundreds, and probably thousands, of deaths since 2010.

Although Sir Stephen praised Pring’s work in highlighting DWP errors over the last 15 years, and his book’s “meticulous accounts” of some of the disabled people who died, he issued a strong defence of his department.

He argued that it was government ministers who were responsible for decisions made by DWP not to release key evidence linking the department with serious harm and deaths.

Sir Stephen pointed last week to the book’s subtitle: How a Violent Government Bureaucracy Killed Hundreds and Hid the Evidence, and he said this implied there was a DWP conspiracy.

He told the committee that the book “doesn’t produce any evidence of the conspiracy” and that he had spent five stints as a minister in the department, and four years chairing the committee, and had “never seen anything that makes me think there’s a conspiracy going on in the department”.

The Department does not claim there was a conspiracy within the department.

Instead, it provides detailed evidence, much of it from DWP’s own records, that shows how a harmful bureaucracy and culture within the Department of Social Security (DSS) and then DWP – its successor – built slowly over the years until it exploded into violence in the post-2010 austerity years.

Sir Stephen also addressed the “hiding the evidence” claim and said there was “a very strong case” for DWP being “much more open in a lot of these areas than has been the case in the past”.

But he insisted that “it wasn’t the department that hid it, ministers chose that things ought not to be open”.

In response, DNS is listing below just a small proportion of the evidence that demonstrates that Sir Stephen is wrong, and how the DWP bureaucracy and culture – including the actions of some of its civil servants – were responsible for the state violence inflicted on disabled people, the majority of it in the last 15 years.

Most of this evidence – although not all – is taken from The Department.

In June 1992, a Dr T P Scott tells fellow DSS civil servant Dr Mansel Aylward, who is leading work to develop a new assessment process for out-of-work disability benefits, of the need for a harsher approach, to “remove the GP from the equation”, and how doing so would remove the need for GPs to have “further arguments with ‘malingerers’”.

In August 1992, a DSS memo reports on a “brainstorming session” among civil servants, led by Aylward, which includes the suggestion that when a claimant fails to attend an assessment without “good cause”, their benefits should be stopped “immediately”, while GPs who allow too many incapacity claims should be identified and even face “sanctions”.

After David Holmes, from Cwmtillery, south Wales, dies from a massive heart attack in November 1996, less than a month after being found ineligible for the new incapacity benefit, Dr Moira Henderson, medical quality coordinator for the Benefits Agency Medical Service, assures colleagues that he had received “an appropriate assessment” from a “totally objective” doctor.

Years earlier, David Holmes had been told by his consultant that he should never work again because if he had “another coronary like the last one, you will never survive it”.

When the National Association of Citizens Advice Bureaux publishes a detailed, evidenced report in March 1997 that suggests many disabled people in poor health “are being caused anxiety, distress and pain” by the new assessment – the forerunner of the work capability assessment – a senior civil servant dismisses the report and tells ministers it is “largely based on anecdotal evidence” and that the issues are “sporadic/isolated”.

Asked why the Benefits Agency did not send an officer to check on the welfare of Timothy Finn, who had a diagnosis of schizophrenia and later starved to death after his benefits were removed, the agency claims in a memo in November 1998 that “this would be seen by many customers as an intrusion of privacy”.

In November 2001, a “malingering and illness deception” conference is held at Blenheim Palace, Oxfordshire, with the organisers later praising the “enthusiastic support” of Mansel Aylward and “funding from the Department for Work and Pensions”.

A book based on presentations made at the conference includes 43 mentions of the word “malinger”, 1,707 of “malingering”, 80 of “malingerer”, and 121 of “malingerers”.

In October 2005, DWP publishes The Scientific and Conceptual Basis of Incapacity Benefits, co-authored by Aylward, which pushes the line that it is not their impairments or the barriers that disabled people face in society that prevent them working, but their own faults, flaws, and unwillingness to work.

The book provides, one researcher will say later, the “intellectual framework” for the government’s welfare reform bill, which is published the following year and introduces the work capability assessment (WCA).

Research by public health experts from the universities of Liverpool and Oxford, will later show that, across England, the reassessment through the WCA of disabled people receiving the old incapacity benefit was associated with an extra 590 suicides between 2010 and 2013.

In November 2012, in evidence for a court case, Dr Bill Gunnyeon, successor to Mansel Aylward as DWP’s chief medical adviser, suggests that asking GPs to provide further medical evidence for all employment and support allowance applicants with mental health conditions would be an “unreasonable… burden”.

DWP documents show how, in 2014, senior civil servants destroy vital documents about the case of Michael O’Sullivan – in breach of the department’s own rules – months after a coroner links his suicide with the WCA.

That decision means DWP is not able to carry out an in-depth investigation – known at the time as a peer review – into the department’s role in his death.

The minister for disabled people in 2014, Mike Penning, later tells DNS that he knew nothing about the decision to destroy the records, and that these decisions were made by DWP civil servants.

Between 2012 and 2014, DWP hides secret peer reviews of deaths linked to the WCA from Professor Malcolm Harrington and Dr Paul Litchfield, the independent experts who between them carry out five reviews of the WCA.

DWP civil servants also fail to show Harrington a coroner’s prevention of future deaths (PFD) report that linked the WCA with the suicide of Stephen Carré in January 2010, and later fail to show Litchfield that report, as well as the PFD that followed Michael O’Sullivan’s inquest.

Errol Graham starves to death in 2018 after his ESA was wrongly stopped in October 2017 because he failed to attend a WCA.

But at the inquest into his death, the documents from his last WCA, in 2014, are left out of the evidence bundle by DWP. They would have shown his “active suicidal thoughts” and how he was “hearing voices in his head all the time”.

The department also fails to share the same documents with a local safeguarding review into his death in Nottingham.

The coroner does not write a PFD report at the end of the inquest because a senior DWP civil servant tells her that a review into its safeguarding procedures will be completed that autumn, with a report to follow.

DWP later admits that no such report was written.

In February 2019, a report by the Independent Case Examiner reveals that DWP failed five times to follow its own safeguarding rules in the weeks leading to the suicide of Jodey Whiting.

Also in 2019, DWP tells the Prime Minister’s Implementation Unit that safeguarding concerns about “vulnerable” claimants of universal credit are only being raised by “stakeholders” and that “the evidence for problems was weak and driven from a campaigning perspective, not an evidence based one”.

In the next two years, the deaths of at least three disabled claimants of universal credit are linked to safeguarding flaws within universal credit.

In January 2021, coroner Gordon Clow highlights 28 separate “problems” with the administration of the personal independence payment system that helped cause the death of 27-year-old Philippa Day.

In April 2022, a disabled woman, Rebecca*, takes her own life after she has been left traumatised by the daily demands of universal credit.

Her mother and brother approach the local jobcentre, 10 months later, to ask for recordings of calls between Rebecca and the jobcentre, but DWP eventually admits that these recordings have been destroyed, in breach of the department’s rules.

In November 2023, whistleblowers from Oxford jobcentre raise serious concerns about DWP safeguarding failures that are putting the lives of benefit claimants at risk.

They also describe how conditions at the jobcentre have become so stressful that 15 of those in one team of 23 work coaches quit within a 12-month period, with at least eight experiencing a significant collapse in their mental health due to a huge, sudden increase in workload in late 2021.

In January 2025, DNS reveals that DWP staff are making thousands of potentially fatal errors every month when dealing with the benefit claims of disabled people, by failing to meet 17 new standards designed to “improve the experience of customers with complex needs and significantly reduce instances of serious cases”.

Most recently, DWP’s chief medical adviser, Dr Gail Allsopp – the latest successor to Dr Mansel Aylward – has dismissed the importance of hundreds of secret DWP internal reviews into the deaths of claimants.

Even though these reviews have led to countless recommendations for local and national improvements within DWP since 2012, she tells MPs on the work and pensions select committee that she views the five deaths in the previous 16 months that have led to a coroner sending the department a PFD report as the only ones “that are associated from a DWP perspective”.

Alison Burton, daughter-in-law of Errol Graham, told DNS this week that she did not believe that it was only ministers who were responsible for DWP’s actions.

She said: “It wasn’t a minister who sat in a chair and removed Errol’s benefits, it was the DWP that made that decision.”

And she said it was civil servants who failed to share key documents with the inquest and the safeguarding review into his death, and who misled the coroner about DWP’s safeguarding work.

She said: “Essentially, the evidence doesn’t point directly to ministers, it clearly points to the civil servants.”

A former DWP work coach, Steven Da Costa, told DNS this week that his experience with DWP between 2020 and 2022 showed there was “a toxic culture that breeds bias and errors into very complex and sensitive situations”.

He said that work coaches in his jobcentre were told at one point that they could order “work capable” universal credit claimants into the jobcentre for meetings five days a week, just to improve attendance targets.

In his resignation email – nine months after he was nearly driven to try to take his own life while at work in a jobcentre, because of the bullying and discrimination he had experienced – he wrote: “The DWP certainly does not have the ‘claimant at the heart of everything we do’.

“Speaking as somebody who has previously undertaken safeguarding and [health and safety] in other roles, the way we seem to be expected to operate and treat claimants is, quite frankly, frightening.”

*Not her real name

Credit for this article goes to the Disability News Service

No responses yet