‘What’s happening to them is the latest episode in the sad saga of discrimination of old: “they’re the same” – all black, gay or Jewish people. It’s seeing the label, not the person. Mostly, in modern Britain, we’ve moved beyond this. Mostly, but not quite. That’s why the Paralympics matters so much. Papa Guttmann is watching.’

________________________________________________________________________________

It’s getting very close. The tension is rising. Over 11 days, around 4,200 athletes from 150 countries will have the London arena, as well as Weymouth for sailing and Eton Dorney for rowing, as their setting for a global audience.

I am talking, of course, about the Paralympics. There’s an appetite. More than 2m of the 2.5m tickets have been sold, and it seems impossible to get hold of the rest. Global television coverage will focus on athletes who have become heroes in their own countries – and who have congenital problems, who are blind or hearing-impaired, or spine-damaged or have lost limbs after accidents.

Though disabled athletes had occasionally taken part in the Olympics before, the Paralympics proper goes back to disasters of the last century. Its real founder was the neurologist Ludwig Guttmann, a German Jewish migrant to Britain who left Germany in 1939 on the eve of war. He settled in Oxford and then in 1944 went to Stoke Mandeville hospital, to treat British servicemen who had suffered spinal injuries.

There, inspired by the 1948 London Olympics, “Papa” Guttmann put his belief in the strengthening power of sport into practice with his own wheelchair-based games. By 1952, the Stoke Mandeville Games had 150 international competitors. In 1960, at the Rome summer Olympics, the competitions were being held in parallel; the term “paralympics” was probably originally meant to refer to paraplegia, but now means “alongside” the Olympics, and was first used officially in 1988.

It’s useful to know all that, I think, as a corrective to any notion that the Paralympics are recent, or “politically correct”. Indeed, the more you think about them, the more inextricably linked they are to the thinking of the mainstream games.

For sport isn’t fair, is it? You need guts and hard work – but you also need the luck of a particular physique. The dominance of Kenyans, Ethiopians and Somalis in long-distance running has a lot to do with geographical altitude and having bigger lung capacity as a result. To be a great sprinter, you need formidable power – you can’t train yourself to be Usain Bolt. Or think of the huge arm-spans (and feet) of great swimmers – you can’t will yourself into the same shape as Michael Phelps, either.

Then there are the other kinds of luck. There aren’t many Indian athletes because India doesn’t care as much about the Olympics as, say, China or Brazil. A talented gymnast shrewd enough to be born in Russia, or the US, would have rather more help and support than one who happens to be born in Chad or Bolivia.

There is a crude, unthinking sports fan who confuses the human lottery with virtue; who worships a Bolt or a Phelps because they are big and physically impressive; or who thinks that Australian or British sportspeople are inherently “better”.

Why waste time talking about it? Because it’s exactly the same kind of stupidity that denigrates other people because they happen to have been born with physical palsy or a learning disability, or to have had a car accident that resulted in both legs being amputated. When it comes to sport, thinking people aren’t particularly interested in the unequal distribution of luck that is part of the human condition; they’re interested in the guts, spirit and staying power.

What’s interesting is what separates out the ones with determination, no self-pity and considerable courage. Some people with Mo Farah’s physical inheritance are presumably lazy. Farah himself, even with his advantages, speaks of a long, long slog to reach the medal podium.

And this is the story of the Paralympics on stilts – or wheels, rather, or blades. These are athletes whose initial store of physical luck was less, but whose determination equals than of a Bolt or a Rebecca Adlington; and whose courage is greater.

If we are prepared to learn about the weird scoring system for diving, or pretend to understand why a little man on a motor-scooter leads the sprint cyclists, because we’re interested in the human stories they reveal, then just the same must apply to the rules and qualifications for wheelchair rugby, or boccia (the boules-style game for people with cerebral palsy) or goalball (for the sightless).

However, the Paralympics may be morally more important than the Olympics. For the stupid adoration of people because of their physical luck has as its flip side the stupid ridiculing or hostility to people because of their disabilities. In essence, it’s the same thing. The comedian’s vile insult, the punch at a bus-stop, the schoolboy mockery of wheelchair-users are all failures of empathy – failures to see the people who are actually there.

And in Britain, at least, this is the time to worry. Official government figures show that the number of disability hate crimes reported to the police in England and Wales has reached a record high – there were some 1,942 last year. That figure has doubled since 2008 and, given the likelihood of the most vulnerable and scared people reporting such crimes, is only a tiny tip of a big iceberg. Other surveys suggest that a fifth of Britain’s 10 million disabled people have suffered abuse or harassment in public.

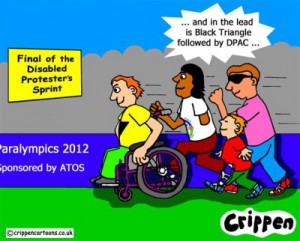

So what’s going on? Charities believe it must be linked to the rise in “scrounger” rhetoric by ministers, and the suggestion that huge numbers of people are dishonestly claiming benefits. In hard times, this is toxic. And because there are always a few bad apples, it is an addictively easy blame game. Yes, there are idle people with disabilities. Yes, there are crooks who happen to be partially sighted. It’s the same with those who aren’t disabled … except that they are a little harder to pick out, and pick on.

As the Paralympics will remind us, there’s a vast range of disability, and it’s people with learning disabilities who are most at risk. According to the Papworth Trust, 90% of them report being bullied, with a third saying it happens every week or every day. These are the people at the sharpest end of the fear and insecurity that comes with hard times.

What’s happening to them is the latest episode in the sad saga of discrimination of old: “they’re the same” – all black, gay or Jewish people. It’s seeing the label, not the person. Mostly, in modern Britain, we’ve moved beyond this. Mostly, but not quite. That’s why the Paralympics matters so much. Papa Guttmann is watching.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.

One response

I would like to point out that these are great observations and I also believe you have identified one of the many problems that surround disabled people as a whole. The other reasons these Paralympics are so important is because it will show that not all disabled are weak, this in turn may give a few people that are disabled courage to face their bullies.

I hope these games change this slightly. Also, I believe if you want a more accurate picture on how many are bullied and how often the most easiest way would be anonymous over the internet.