Home > Benefit Litigation , Conflicts of Interest , Employee Benefit Plans , Fiduciaries , Standard of Review > Stephan v. Unum, the Attorney-Client Privilege, and the Need for Independent Counsel for Company Officers and Plan Fiduciaries >

September 13, 2012 Posted By Stephen D. Rosenberg

September 13, 2012 Posted By Stephen D. Rosenberg

Tidal Wave! Landslide! Look out below!

Pick out the metaphor of your choice, because Unum just got taken out behind the woodshed by the Ninth Circuit and spanked hard.

Frankly, the Ninth Circuit’s opinion is a rout in favor of the participant, and participants in general.

In many ways, the case presented a perfect storm for such an overwhelming opinion against a long-term disability carrier.

The case involved: a very sympathetic plaintiff who suffered a horrible, fluke injury that most readers could sympathize with; a lot of money; and a long-term disability carrier with a documented history of claim disputes that the court could point to in further support of its ruling.

I have to tell you that the facts painted by the Ninth Circuit in this opinion, related to both the claim and the carrier, are clearly of an outlier event, one not representative of the handling of most claims by most long-term disability carriers, or of most long term disability carriers at all, for that matter.

Twenty years of experience tell me most attorneys representing participants would, even if only off the record, agree with that assessment.

Frankly, despite Unum’s own documented history with regard to claims handling, cited by the Ninth Circuit to support its opinion, I am not sure that the depiction of the carrier in this opinion is even representative of that carrier at this point in time, but I don’t know enough to comment knowingly in that regard.

More importantly though, and moving away from the overflowing kettle of clichés with which I deliberately chose to fill the first couple paragraphs of this post, it would be a shame if courts, participants, companies and their lawyers allowed the unusual nature of the case to become the focus of their attention.

This is because there are several key takeaways from this case, some specific to long-term disability cases and others, even more important, to ERISA litigation in general.

With regard to these types of benefit claims, one should look closely at the Court’s handling of the structural conflict of interest issue.

The Court not only points toward significant discovery and even a possible bench trial over this issue, but also demonstrates how to use the contents of an administrative record in support of proving the impact of such a conflict.

This is all strong stuff, and for many who thought the Supreme Court’s structural conflict of interest ruling in Glenn opened up a Pandora’s box or put us all on a slippery slope towards ever expansive, and more expensive, benefits litigation, here is the proof for that hypothesis.

To me, the most worrisome aspect of the decision, and one that sponsors and companies need to pay very careful attention to in terms of planning their benefit operations and obtaining legal services, is the Court’s very broad application of the fiduciary exception to the attorney-client privilege.

The issue here isn’t so much the conclusion that the exception makes internal legal discussions related to a claim subject to disclosure, but the line drawing it demonstrates with regard to when legal advice is, and is not, subject to disclosure.

In short, plan administration – including benefit determination issues – are subject to disclosure and not protected.

At the same time, though, what is protected is advice related to the protection of fiduciaries against personal liability, civil or criminal, when that advice is clearly distinct from the handling of claims under a plan and the administration of a plan.

Now the interesting thing about that distinction is that, as anyone who litigates breach of fiduciary duty or other ERISA cases knows, there is clearly some overlap between the two types of legal advice and there is not always a clear separation between the two.

Certainly a fiduciary sued for misconduct is being sued because of events involving a claim and a plan’s administration, and thus legal advice rendered to the fiduciary falls somewhere in the middle of those two extremes.

Further complicating this issue is a fact that the Ninth Circuit points out, which is that plan sponsors and plan fiduciaries often rely on the same lawyers and law firm for advice on all aspects of their plans, from formation to termination and everything in between, including the handling of claims and the representation of officers sued as fiduciaries.

In that latter instance of breach of fiduciary duty litigation against officers, it is crucially important for numerous reasons, as every litigator knows, to have a safe, secure and fully privileged attorney-client relationship.

The standards enunciated by the Ninth Circuit, however, place that privilege at some risk in instances in which the same firm that has represented the plan in general is also representing fiduciaries or other company officers with regard to their personal potential liability.

The best answer, for numerous reasons, to protecting those fiduciaries and officers, and maintaining the attorney-client privilege that is crucial to their protection, is going to be separating out the representation of such individuals from the routine legal work related to the plan’s formation, operation, administration and claims handling, and using independent, distinct counsel for the representation of such individuals.

By segregating out and using separate, independent counsel for any issues related to their potential exposures, you make clear that the legal advice at issue involves privileged issues concerning the potential liability of officers and fiduciaries, which should still be privileged after the Ninth Circuit’s ruling, and is not intermingled with or otherwise part of the broad range of legal services typically required by a plan, which the Ninth Circuit’s opinion holds is likely to be subject to disclosure.

In short, the pragmatic solution is to continue to use one firm for the overall handling of a plan’s various needs, but separate, independent counsel for any and all needs – whether involving litigation or only the potential risk of litigation or exposure – of a plan’s fiduciaries or the officers of the company sponsoring the plan.

That’s my two cents for now.

The case is Stephan v. Unum, and you can find it here.

One response

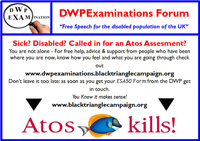

unum cant be trusted and should be outlawed everywhere as they will not pay out wake up mps its over here withholding out its hands in every profitable outfit it can make up like paying unis to help it with the welfare state how lovely they take our benefits away also jeff3