Disability News Service

By John Pring, Disability News Service, 24 October 2012

An award-winning disabled artist is to spend three days in bed in front of an audience, in an attempt to portray the contradictions of her impairment, and the government’s “miserable, terrifying, punishing” fitness for work assessment regime.

The writer-director-activist Liz Crow is forced to spend much of her life in bed because of her impairment, but has always managed to keep that part of herself hidden from view.

“I have developed this incredibly stark way of living,” she says, “and what other people see of me in public spaces is not how I am for most of my life. Even the people close to me don’t really know me at the most extreme.”

In Bedding In , she will make her “twilight existence visible”, exposing the part of her life she spends in bed to public scrutiny, and for the first time “parading” this private self in public.

The piece, part of this year’s SPILL Festival of Performance, in Ipswich, is Crow’s response to the government’s harsh benefits reassessment programme.

But rather than lying low for fear of being penalised by the Department for Work and Pensions, she has decided to “stare that fear in the face”.

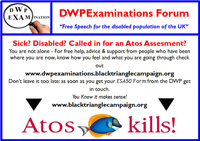

She is one of the hundreds of thousands of long-time incapacity benefit claimants who have been tested through the government’s reassessment programme, and subjected to the infamous work capability assessment, carried out by the government’s contractor Atos Healthcare.

Even though Crow has used a wheelchair for 26 years, Atos decided that she had no difficulty walking. She was placed in the work-related activity group (WRAG), for those thought able to move towards paid work.

But she knows she cannot make herself available for work, and so – unless she wins her appeal – she has resigned herself to having her benefits taken away because of the inevitable failure to co-operate with the regime.

“The consequences are that I may have no income coming in and don’t know how as a single parent I will care for my child, let alone my home, etc.”

Less than two weeks after her performance ends, she will need to parade her private self again, when she appeals to a tribunal against the decision to place her in the WRAG.

Crow is clear that she wants Bedding In to be about the complexity of her impairment, and not its “tragedy”.

“I live a pretty good life with the complicated set of circumstances that I have got,” she says, “but if I step out of my bed then it is not seen as complexity or contradiction, and in the current benefits system it means you fall through the gaps.”

Each day during the performance at Ipswich Art School Gallery, members of the public will gather around her bed to discuss the work, and its politics. The hope is that Crow will take the “data” from these conversations and use them to further develop the piece.

“It is a political statement,” she says of the performance, “but it is also trying to make visible this kind of internal wrestling that goes on for a lot of us with the benefits stuff.

“Since I got personal assistants 15 years ago I have managed to find a kind of fragile security in my life. I have rarely earned but I have, I hope, contributed.

“Now the benefits thing has kicked in it has all gone. Suddenly I don’t feel I have any security left whatsoever.”

Even if she wins her appeal, she faces the likely prospect of being reassessed again in another year or so, and then again, and again.

“The idea that this is life now: that is just dire. There are hundreds of thousands of us going through this assessment. There is some small comfort that there are a lot of us in it together but it is not much comfort because of the toll it takes.

“I have this tiny amount of time when I am well enough to do stuff and I am looking at that time being taken away.

“It has been really hard to create the life I have got, a reasonable life, and this big system comes along with these politicians who are so extraordinarily removed from a life like mine and they demolish what I have built up.”

The whole process feels, she says, like “punishment”, not assessment, “an endless round of justifying myself and fighting for a grain of security”.

“There are layers and layers of why it is so hard. One of the things is that if you fall through the gaps, for the press it is evidence that you are a scrounger and a fraudster.”

She is among the many disabled activists who believe that this cruel assessment process – and the callous and incompetent way it is carried out by Atos – are responsible for the premature deaths of hundreds, if not thousands, of disabled people.

Even if these deaths are not caused by the process, she says, “actually they died among all this shit, their last few months were so miserable and so frightening, and I think that’s unforgivable. To condemn people to a really miserable last few months is diabolical.”

Crow feels there is an affinity between her performance and the direct action protest carried out by members of Disabled People Against Cuts (DPAC) at Marble Arch in central London last weekend.

One of the reasons she is so impressed with DPAC’s campaigning work, she says, is that “they have created an incredible visible presence but have found ways for all sorts of people to contribute”, particularly through social media.

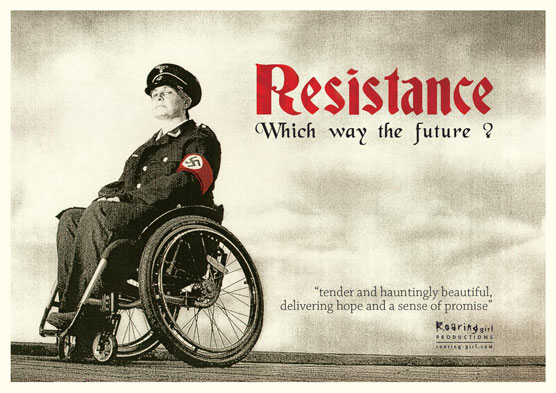

She also sees links with her most recent piece of work, Resistance, an award-winning video installation about the Aktion-T4 programme, which led to the targeted killing of as many as 200,000 disabled people, and possibly many more, in Nazi Germany.

She began working on Resistance in 2008, and started thinking about its themes several years earlier, and felt even then that there were contemporary “connections”.

“Those contemporary connections have just got stronger and stronger,” she says. “I am appalled to feel that we are under greater threat now than we have been in all the years I have been involved in activism.”

She points to newspaper reports of alleged disability benefit fraud and the use of language like “shirkers”, “scroungers” and “fakers” to describe disabled people. This kind of propaganda, she says, is “eerily familiar” from descriptions of pre-Holocaust Germany.

The “specifics” of what is happening now are not the same as in Nazi Germany, she adds, but “the values beneath it are, this idea that we are somehow dispensable, more dispensable than others”.

She also points to the Paralympics, which she says “makes the scrounger-fraudster rhetoric stronger, and leads to a backlash”.

There are even similarities between the Paralympic classification system, and the benefits assessment system. Both suit those who have a “bio-mechanical, quantifiable impairment”, rather than less clear and easily-determined impairments.

Would-be Paralympians with “nebulous impairments” fall through the gaps, she says, just as she and many tens of thousands of other disabled people have fallen through the yawning gaps in the benefits system.

Bedding In is part of Disability Arts Online’s Diverse Perspectives project, which is funded by Arts Council England, and is commissioning eight disabled artists to make new artwork that “sparks conversations and debate about the creative case for diversity”.

Bedding In takes place at the Ipswich Art School Gallery from 1-3 November, from 11am to 6pm, as part of the SPILL Festival of Performance in Ipswich.

One response

Good on her.