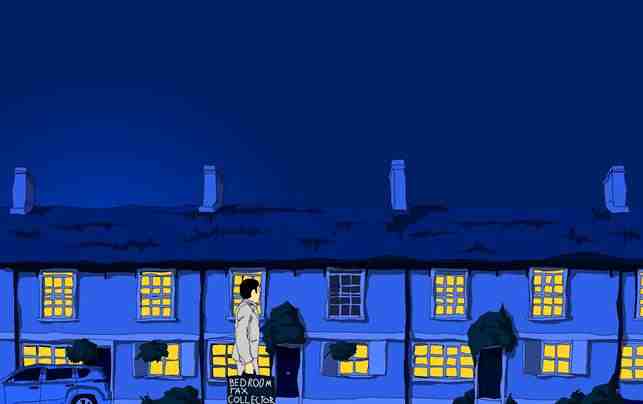

The ‘London Clearances’ gathers momentum: To get a two-bed place in Tower Hamlets you need more than double the median household income. Meanwhile, benefits are capped and ‘spare’ bedrooms are taxed while there remains a chronic shortage of single-bedroom accommodation.

by Owen Jones

I already knew that Britain was in the throes of an escalating housing crisis, but, on the move for the first time in two-and-a-half years and, having been protected from soaring rents by a benevolent landlord, I was in for an unwelcome meeting with reality. Looking for a modest two-bedroom place in London’s Zone 2 – with a housemate who, appropriately enough, works for a housing charity – I found that a standard monthly individual rent was £800, even £900. One estate agent asked what our maximum budget was: when I suggested £700 each a month, he spluttered down the phone. How many can actually afford – and I mean “have sufficient money left over to have a decent existence after paying the landlord” – these sorts of rents?

Inevitably, I took to Twitter to vent. I was stunned by the response. Hundreds of furious Londoners bombarded me with their renting horror stories. One had a 35 per cent rent hike imposed on them at Christmas; another was forced to desert their Stockwell flat after a 40 per cent increase. “My tiny flat in the East End went up by £200 a month for the next occupants when I left,” freelancer Scott Bryan tweeted me. “It was £600 already. Eyewatering.” Another abandoned their own “tiny flat” in Zone 3 after their monthly rent went from £720 to £950.

Private landlords can do as they please, of course. Having a roof over your head is a basic human requirement and, when there is a lack of houses to go around, it is a need that can be exploited. A landlord knows that, if their tenants don’t like an outrageous rent hike, their only option is to put themselves back at the mercy of the ever more pricey private renting market.

According to Shelter, annual rents in inner London went up by 7 per cent last year – or just under £1,000 for a two-bedroom house. When people’s wages are flat-lining, that’s a big hit. Of course, some landlords – like mine – can be benevolent; others ruthlessly profiteering. It is a complete lottery.

I’m no victim. I can afford a high rent, even if it rankles. That is not the case for most. The number of us privately renting has soared: One in six households now have private landlords. And it is no longer largely the preserve of students and young people. Indeed, the number of families with children forced to privately rent has nearly doubled in just five years to more than a million. They face the prospect of having to repeatedly move, disrupting the education and overall wellbeing of their kids.

Greedy landlords are fully aware that most cannot afford to pay their extortionate rents. But they also know that the taxpayer will step in and subsidise them with housing benefits. According to the Homes for London campaign, to get a two-bed place in Camden, you need an average monthly household income of £5,324; in Tower Hamlets – one of the poorest boroughs in Britain – it’s £4,333, way over double Britain’s median household income. It’s the state that tops up the difference. Back in 2002, 100,000 private renters in London were claiming housing benefit; it soared to 250,000 by the time New Labour was booted out.

The 21st Century version of The Highland Clearances continues

But Cameron’s Government has decided to punish the tenant, imposing a housing benefit cap that will force many out of their homes. London is on course to be more like Paris: with a centre that is a playground for the affluent, while the poorest are confined to the edges.

Here are the consequences of Thatcher’s ideological war on council housing. Her mentor, Keith Joseph, argued right-to-buy would spur on “embourgeoisement”. Instead, it has left five million people languishing on social housing waiting lists, and millions at the mercy of private landlords. Council housing has been intentionally demonised as something to escape from, and the lack of stock to go around has left it prioritised for those most in need. We’ve come far from Nye Bevan’s vision of council housing supporting mixed communities, replicating “the lovely feature of the English and Welsh village, where the doctor, the grocer, and the farm labourer all lived on the same street”.

But rather than leave millions at the mercy of the mini autocrats of the rented sector, a new wave of council housing would offer accountable landlords, without the absurdity of market rates. Instead of wasting billions on housing benefit, we could spend it on building housing, creating jobs and stimulating the economy.

We could learn a lot about private renting from Germany. Local government sets the maximum rent for flats. The landlord cannot arbitrarily impose dramatic hikes; increases can only come in regulated steps. Such a solution would be good for the British taxpayer, bringing down the housing benefit bill without kicking the tenant. This ever-worsening housing crisis is just a striking example of a society based around the needs of profit, rather than people.

We were told the free market would liberate the individual: instead, it leaves them trapped by the whims of landlords, financially less free, and banished from entire communities. It is a con – and an expensive con at that.

One response

And of course all the extra money being paid for higher rents is being taken out of the local economy as tenants cut down on other spending.