From Malthus to Ian Duncan Smith

By Susan Pashkoff

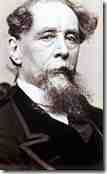

It is the bicentennial of the birth of Charles Dickens and I find myself with a strange feeling of déjà vu listening to politicians in the UK.

When we think of Oliver Twist, Great Expectations, or A Christmas Carol to name a few of the wonderful things that Dickens wrote, somehow we think that we are past the time when the following exchange would still bring a chill to the bones and fear rising from our feet to the top of our head:

“At this festive season of the year, Mr. Scrooge,” said the gentleman, taking up a pen, “it is more than usually desirable that we should make some slight provision for the Poor and Destitute, who suffer greatly at the present time. Many thousands are in want of common necessaries; hundreds of thousands are in want of common comforts, sir.”

Scrooge by Michael McKenzie

“Are there no prisons?” asked Scrooge.

“Plenty of prisons,” said the gentleman, laying down the pen again.

“And the Union workhouses?” demanded Scrooge. “Are they still in operation?”

“They are. Still,” returned the gentleman, “I wish I could say they were not.”

“The Treadmill and the Poor Law are in full vigour, then?” said Scrooge.

“Both very busy, sir.”

“Oh! I was afraid, from what you said at first, that something had occurred to stop them in their useful course,” said Scrooge. “I’m very glad to hear it.”

“Under the impression that they scarcely furnish Christian cheer of mind or body to the multitude,” returned the gentleman, “a few of us are endeavouring to raise a fund to buy the Poor some meat and drink and means of warmth. We choose this time, because it is a time, of all others, when Want is keenly felt, and Abundance rejoices. What shall I put you down for?”

“Nothing!” Scrooge replied.

“You wish to be anonymous?”

“I wish to be left alone,” said Scrooge. “Since you ask me what I wish, gentlemen, that is my answer. I don’t make merry myself at Christmas and I can’t afford to make idle people merry. I help to support the establishments I have mentioned — they cost enough; and those who are badly off must go there.”

“Many can’t go there; and many would rather die.”

“If they would rather die,” said Scrooge, “they had better do it, and decrease the surplus population. Besides — excuse me — I don’t know that.”[i]

Many understand and heartedly endorse the idea that even the poor deserve a nice Christmas, but what about the rest of year?

What are the rights of the poor and disabled people?

What is our responsibility to them as human beings?

In the current debate on welfare reform in the UK we are not only hearing the echoes of the past, we are watching the re-enactment of the failed policies to address the poverty that derives from the essential nature of the capitalist system.

Welcome to modern Britain.

A man in a coma is declared fit for work,[ii] a man with terminal cancer is fit for work, and people have committed suicide facing ATOS testing and appeals.[iii] The rhetoric against benefit scroungers is so harsh, that disabled people are being abused, harassed on the streets, and facing further alienation.[iv]

Listening to discussions in the government for the reform of disability benefits and welfare it is evident that while they claim to have new ideas, all they are doing is recycling the inadequate analyses of the 19th century that failed the poor and the working class so horrifically.

Iain Duncan Smith

Work and Pensions Secretary Iain Duncan Smith said: “Our reforms will end the absurdity of a system where people too often get rewarded for doing the wrong thing, and those who strive to do the best by their families get penalised.

“The publication of the Welfare Reform Bill will put work, rather than hand-outs, at the heart of the welfare system.”.”[v]

Let’s look a little closer at the Welfare Reform Bill:

The main elements of the Bill are:

• The introduction of Universal Credit to provide a single streamlined benefit that will ensure work always pays (annual benefit cap of £26,000 per family)

• a stronger approach to reducing fraud and error with tougher penalties for the most serious offences

• a new claimant commitment showing clearly what is expected of claimants while giving protection to those with the greatest needs

• reforms to Disability Living Allowance, through the introduction of the Personal Independence Payment to meet the needs of disabled people today

• creating a fairer approach to Housing Benefit to bring stability to the market and improve incentives to work

• driving out abuse of the Social Fund system by giving greater power to local authorities

• reforming Employment and Support Allowance to make the benefit fairer and to ensure that help goes to those with the greatest need

• changes to support a new system of child support which puts the interest of the child first. [vi]”

This almost sounds harmless until you look and see what they are proposing and the roots of the arguments that they are using to justify these welfare reforms.

The primary change is the introduction of a benefits cap; this benefits cap is limited to £500/week or £26,000/year. That sounds pretty generous, except, that this cap is on all benefits, these include housing benefit, child benefit, sickness benefit, disability benefit, carers benefit, along with welfare and food benefit.

“From 2013 the Government will introduce a cap on the total amount of benefit that working-age people can receive so that households on out of work benefits will no longer receive more in benefit than the average weekly wage earned by working households.

The cap will apply to the combined income from the main out-of-work benefits (Jobseeker’s Allowance, Income Support, and Employment Support Allowance) and other benefits such as Housing Benefit, Child Benefit and Child Tax Credit, Industrial Injuries Disablement Benefit, Carer’s Allowance (unless a member of the household is entitled to Disability Living Allowance, Personal Independence Payment, Attendance Allowance or Constant Attendance Allowance). […] In Work Credit, which can be paid to lone parents, and Return to Work Credit, which can be paid to those leaving incapacity benefits, are intended to act as work incentives and so will also not be included when calculating benefit income.[vii]”

The idea behind the limit is that these benefits are disincentives for people getting jobs; those on benefit should never have an income higher than those that actually are working. Moreover, underlying this argument is the idea that people are not working because they are slackers that are taking advantage of the generosity of the welfare system and the taxpayer.

“Launching a staunch defence of his welfare reforms, the Work and Pensions Secretary argued that some households on benefits were “trapped” in homes that they would not be able to afford if they worked. He added: “They therefore are discentivised from taking work. They are incentivised, many of these families, to find more children so that they can stay out of work. This is utterly wrong and it’s a benefit system which desperately needs change.”[viii]

In fact, it is assumed that those on benefit (those on welfare and disability) could be working, but the existence of benefits means that they are not going to work as it is not in their interests. Underlying this argument of course is the idea of deserving and undeserving poor; this is an old theme. However, the problems with this old theme and its resuscitation, is that unemployment is part and parcel of the capitalist economic system.

These people are not voluntarily unemployed irrespective of how much the so-called reformers insist upon it. Simply put, there are no jobs.These people are not sitting home voluntarily; they are involuntarily unemployed. In the case of those on disability, not only are they being accused of being voluntarily unemployed and capable of work, they are essentially being cleared for work (commensurate with loss of benefit) when there is no work.

There are other major problems as well, specifically:

1) the amount available includes housing benefits, this means that people living in the centre of London or in wealthier areas or areas undergoing gentrification will certainly not be able to afford the rent; this means that they will need to relocate to areas where rents are not as high, leaving the centre of London a nice white wealthy area.

“At lower percentiles of the market, the cap will still make some parts of the country unaffordable on Housing Benefit alone for larger households receiving benefit and it is difficult to accurately predict what will happen to the affected households, as it depends on households’ behavioural responses and on the availability of accommodation. The impact on those affected will be that they will need to make a choice between a number of options including starting work, reducing their non-rent expenditure, making up any shortfall in Housing Benefit using a proportion of their other income or moving to cheaper accommodation or area. The Government is looking at ways of easing the transition for families and providing assistance in hard cases.[ix]”

2) Larger families do not get increased benefits for each child after a certain number; that means that larger families are those exactly that will be penalised.

“Approximately 40% of households who are likely to be affected by the cap will consist of five or more children whilst over 80% will consist of 3 or more children. Fewer than 10% of households likely to be affected by the cap will consist of no children at all.[x]”

3) Again, single parents will feel the impact the worst, the DWP admits this and also that these are primarily women:

“Based on internal modelling using the Department for Work and Pensions’ Policy Simulation Model, we expect around 60% of customers who are likely to have their benefit reduced by the cap to be single females but only around 3% to be single men. Most of the single women affected are likely to be lone parents, this is because we expect the vast majority of households affected by this policy (around 90%) to have children. Approximately 60% of those who will be capped are single women. Single women form around 40% of the overall benefit population. However, the impacts of the cap on women, can be mitigated by the support available to help lone parents move into work and become eligible for Working Tax Credit which will make them exempt from the cap. (As stated we expect the vast majority of single women affected by the cap to be lone parents and so eligible for this help.) Lone parents can become eligible for WTC when working 16 hours or more a week, so putting them at an advantage to those who have to work at least 30 hours a week. The Department is considering what mitigation might be appropriate once Working Tax Credit has been incorporated into Universal Credit.[xi]”

4) Unsurprisingly, this will affect ethnic minorities more:

“People from ethnic minority households are also more likely to be in receipt of an income-related benefit than those from a white household. This affects some groups in particular: 30 per cent of Pakistani and Bangladeshi households are in receipt of an income-related benefit compared with 19 per cent of white households. Based on internal modelling using the Department for Work and Pension’s Policy Simulation Model, we estimate that of the households that are likely to be affected by the cap, approximately 30 per cent will contain somebody who is from an ethnic minority. Ethnic minorities form less than 20 per cent of the overall benefit population. In mitigation of the impact, from 2011, customers from all ethnicities will receive help in finding work from the Government’s new Work Programme. This will be the biggest single welfare to work programme this country has ever seen. It will be built around the needs of individuals, providing them the right support at the right time.[xii]”

The debate over this reform has been very instructive.

The Lords have tried to dilute the bill and have amended it trying to exclude child benefits from the benefit cap (this was led by the Bishops of the Church of England), tried to prevent single parents being charged for using the child support agency to collect maintenance from the fathers of the children and have also tried to ensure that the replacement of disability living allowance by a new system is done only on trial for one year.[xiii]

In response, the government has overturned the Lords amendments and banned further dissent by taking the rare step of declaring “financial privilege” that asserts that only the Commons has the right to make decisions on bills that have large financial implications.[xiv] However, Iain Duncan Smith (the minister of work and pensions) has offered three concessions backing down on the £50 fee for parents on out of work benefits to get help claiming maintenance from the other parent; a 9 months “grace period” to adapt to the loss of benefits to find a job or move home; and a discretionary fund for local authorities so that children will not be forced to move during a critical stage in their schooling.[xv]

Of course, no mention is made of the impact on schooling in those areas in which these families are being forced to move.

The rights of the poor and the late 18th and 19th century

In many senses, while people are talking about Dickens, what they are missing is that we have returned to an old debate about the rights of the poor and disabled … what Dickens was discussing in the Victorian period actually had its roots further back in the past; we need to go all the way back to 1795-7 and the reform of the old poor law to actually try to deal with poverty that was associated with the rising capitalist economic system.

Older economic arguments and social policy raised the question of the notion of social subsistence as that underlying the determination of wages and the fact that poverty was a result of the failure of the economy to provide employment for all; unemployment was recognised to be part and parcel of the economic system.

Following bread riots, food riots a reform of the Old Poor Law relating to capitalism (rather than feudal or mercantilist Britain) lasted from 1795-7 to 1834. From the passage of the 1795-7 Poor Law Reform, political philosophers and political economists altered the discussion of the rights of the poor significantly.

This was a two-pronged process: A change in how wages were viewed as determined was undertaken. Instead of wages being determined by historical and social subsistence and employment being determined by the amount of capital available for employing labour, the discussion was shifted.

Wages were instead flexible determined by the quantity of capital available for the employment of labour (demand) and the available labouring population (supply).

As such, the greater supply of labour means lower wages of labour; these are determined by the market independent of social subsistence.

This changed the theory of employment from one recognising that unemployment derived from insufficient accumulation of capital towards one where it derived from too many labourers.

It was the labourers fault if wages were too low, they bred too much.

The new theory was a full employment theory, all labour could be employed at the going wage; obviously if people were not working this was by choice.

Poverty and unemployment were not the fault of the economic system; they were the fault of the poor themselves. It was their laziness and immorality that was the cause of their poverty.

Economists went so far as to argue that it was easier to increase population as opposed to capital (see James Mill, 1826, chapter 1).

Nassau Senior

Nassau Senior (see left) argued that the poor law enabled wages to be determined outside of the market; the Speenhamland system meant that the worker is free without the disadvantages of freedom: according to Senior, he is free from the brutality of slavery but is guaranteed the subsistence of the slave, he is expected to save money although his relief increases with the size of the family, he is expected to work hard although he has no fear of starving, he is attached to an employer by state law, and receives an allowance which he views as a right (Senior, 1831, ix).

The unemployed and poor were lazy, immoral, and dissolute. They bred beyond what they could support, they did not want to work, and they took but did not contribute … they were a curse on the nation.

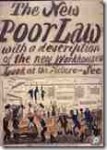

The New Poor Law (1834), made out-door relief (relief outside the workhouses) illegal; thereby forcing the poor into workhouses and in the process separated parents from their children. Based upon the principle of lesser-eligibility (which we will discuss below in detail), this formed both the new criterion for assistance for the poor.

The New Poor Law was in use until it was finally completely abandoned with the elimination of the Poor Law (1930) and the closure of workhouses. Even though they were closed formally in 1930, people still resided in them[xvi] and it was not until the creation of the National Assistance Act of 1948,[xvii] and the creation of the social welfare state that the last workhouse was closed. The social welfare state is facing the culmination of a long term attack starting in the 1970s.

The attack on the rights of the poor:

The feelings of déjà vu that I am having are for good reason; the arguments justifying it were the same ones used to bring down the Old Poor Law. Quite honestly, the same language of deserving and undeserving poor, relief creating disincentives to work, conditions of life being worse for the poor and disabled than those incomes obtained by those working, the laziness (idleness) of the poor, the immorality of the poor, the need for these people to be made to work is almost identical to the points raised against the old poor laws by Bentham, Malthus and Nassau Senior.

So what was in the Old Poor Law that was odious?

Old Poor Law:

“Let us, said he, make relief a matter of right and honour, instead of a ground for opprobrium and contempt. This will make a large family a blessing and not a curse; and will draw a proper line of distinction between those who are able to provide for themselves by their labour, and those who, after having enriched their country with a number of children, have a claim upon its assistance for their support (Pitt, 17/2/1796, p. 370 in Pitt, 1806, Vol. II).”

“The law which prohibits giving relief where any visible property remains should be abolished. That degrading position should be withdrawn. No temporary occasion should force a British subject to part with the last shilling of his little capital, and compel him to descend to a state of wretchedness from which he could never recover, merely that he might be intitled to a causal supply (Pitt, 17/2/1796, op cit., p. 372).”

Massive amounts of discontent, food riots, and destruction of crops lead to the reform of the Poor Law. Poverty in rural sectors was, at times, at starvation levels arising from the high amount of seasonal unemployment, and the restructuring of agricultural production (which included the introduction of labour displacing machinery).

The Poor Law Amendments of 1795-7 were primarily concerned with the alleviation of poverty in the rural areas. Additionally, the relaxation of the laws of settlement attempted to allow for the migration of labour from areas with little employment opportunities (agriculture) to other regions of the country (manufacturing), where they might be able to obtain employment.

Under Pitt (the younger) and the Tory party these amendments enabled relief to be obtained outside of the workhouses (“outdoor relief”), pegged relief to the size of the family and food (wheat) prices,[xviii] and attempted to deal with seasonal employment in agriculture by providing for wage supplements during periods of labour inactivity.

Under Pitt (the younger) and the Tory party these amendments enabled relief to be obtained outside of the workhouses (“outdoor relief”), pegged relief to the size of the family and food (wheat) prices,[xviii] and attempted to deal with seasonal employment in agriculture by providing for wage supplements during periods of labour inactivity.

A Cow Money Clause was introduced to enable the poor to purchase a cow if they had access to land; this was in response to the fact that enclosures of the Commons had affected the diet of the poor substantially, with milk falling out of consumption in some areas.

This was seen as a way to give people a manner of obtaining subsistence (and a more balanced diet), after which they would not obtain any more relief. In order to be eligible for this money, they had to be recommended by two justices of the peace in their parish.

The law which prohibited giving relief where visible property remained was withdrawn so that people that actually owned something would not be forced to sell it to get relief during hard times.

In addition, these amendments also allowed for the relaxation of the 1622 Laws of Settlement (Poor Law Removal Act). The 1622 Laws of Settlement only allowed for relief in the county or parish of birth or after residence of four years. Prior to the enactment of this legislation, workers were often removed from their new place of residence prior to their becoming eligible to receive relief.

The reformed act forbade the eviction of the poor until they became chargeable and made the parish ordering the move to pay the expenses of the removal.

The provisions for settlement allowed the workers to obtain relief in the cities. These changes enabled freer labour mobility and allowed workers to get relief in the new residence after only 4 months and denied the right of the parish to forcibly remove people who could become eligible for relief.

This bill allowed for the alleviation of tensions in the countryside and the cities, as unemployed rural workers could migrate to the cities where they could find employment, and could obtain relief between employments.

There were additionally changes made in the Laws of Bastardy. The relaxation of bastardy laws made the father, as opposed to the mothers, primarily responsible for the care of the child which considerably helped women to care for their children without having to go on Poor Relief.

The Attack:

From the moment of its passage the reformed poor law came under attack. There are two people that led this attack, Jeremy Bentham and Thomas Robert Malthus. Both of these men have influenced the modern debate on the rights of the poor and the responsibility of society to assistance.

However, it is Bentham whose ideas are forming most of the contemporary discussion on welfare reform, although Malthus rears his head periodically (see the quote above from Duncan Smith about the poor having children to get benefits).

However, it is Bentham whose ideas are forming most of the contemporary discussion on welfare reform, although Malthus rears his head periodically (see the quote above from Duncan Smith about the poor having children to get benefits).

Bentham

“A person deprived of all his limbs, or the use of all his limbs may still possess ability sufficient to the purpose of serving as an inspector to most kinds of work, so long as his mental faculties, and sight for observing, and voice for questioning are possessed by him in sufficient rigour (Bentham, 1796, p. 46-7).”

The discussion of the rights of the disabled and the rights of the poor are in many senses inseparable. Although theoretically separate; the separation between “deserving” and “undeserving” poor are discussed in great detail by Bentham as this is essential to his argument. However, while he spends a lot of time on this distinction, he often argues that irrespective of the distinction, work is the answer for all.

Bentham begins his discussion by distinguishing between two fundamental things, poverty and indigence.

According to Bentham, poverty (the state of having no recourse to property) is thegeneral state of mankind. It is the fact that the vast majority of humanity does not own property that forces them to sell their labour to obtain their subsistence.

Bentham never questions the fact that there are those who do have recourse to property, nor does he discuss how they came to be in this situation; he takes the fact that this is the situation as his starting point. Given this, he argues:

“As labour is the source of wealth, so is poverty of labour. Banish poverty, you banish wealth: banish all those who are liable to become chargeable, you banish all those who are either disposed or qualified to become serviceable. If labour is liable to cease, so is property to be destroyed or spent […] (Bentham, 1796, pp. 3-4).”

As such, according to Bentham, since poverty is the natural and unchangeable lot of man (Bentham, 1796, p. 3), the proper subject is not the elimination of poverty, but rather thealleviation of indigence:

“Indigence, therefore, and not poverty, is the evil, the removal of which constitutes the proper object of the Poor Laws. To banish poverty, is an attempt founded in inadvertence, and which, in the nature of things, must have either no effect or a bad one. Indigence may be provided for: mendacity may be extirpated: but to extirpate poverty would be to extirpate man (Bentham, 1796, p. 4).”

Bentham introduces the notion of eligibility rather than entitlement to address the question of who should have access to relief; he established a criterion for the amount of relief that the poor would be entitled:

“Position 16: If the condition of individuals, maintained without property of their own, by the labour of others, were rendered more eligible than that of persons maintained by their own labour, then, in proportion as the existence of this state of things were ascertained, individuals destitute of property would be continually withdrawing themselves from the class of persons maintained by their own labour, to the class of persons maintained by the labour of others; and the sort of idleness which at present is more or less confined to persons of independent fortunes, would thus extend itself, sooner or later, to every individual of the number of those on whose labour the perpetual reproduction of the perpetually consuming stock of subsistence depends: till at last there would be nobody left to labour at all, for any body (Bentham, 1796, p. 39).”

He is convinced that society will in fact collapse as people clearly will never labour if they can avoid it. Bentham clearly believes that people are inherently lazy and prefer idleness and that if they can obtain their social subsistence without labour, they will do so. If people are not forced labour, there will no longer be the continual creation of commodities and the society and economy will collapse.

“Position 17: The destruction of society would therefore be the inevitable consequence, if the conditions of persons maintained at the public charge were in general rendered more eligible, upon the whole, than that of persons maintained at their own charge, those of the latter not excepted, whose condition is least eligible (Bentham, 1796, p. 39).”

It is the notion of lesser eligibility that forms the basis for the amount of relief and also the condition of people forced into the workhouse and is adopted as a template by the reformers behind the 1834 Poor Law Amendments. As such, the conditions in the workhouses and the amount received as relief must be worse than the normal conditions of labour and the level of wages received.

Bentham describes in detail the deserving and undeserving poor, he separates those that are physically disabled, mentally disabled, the elderly, and children whom he describes as deserving of relief (but if they can be brought into work, so much the better) from those that are able-bodied (that are obviously lazy and living off the labour of others).

“Position 23: To a person possessed of adequate ability, no relief ought to be administered, but on condition of his performing work: to wit such a measure of work as, if employed to an ordinary degree of advantage will yield a return, adequate to the expense of relief (Bentham, 1796, pp. 44-5).”

For minors (and this is creepily reminiscent of a recent statement by Newt Gingrich), the issues of make the little swine work is raised (irrespective of his saying that children are entitled to relief):

“Position 47: From the labour of a Minor, brought up and educated at the public charge, the public may, without injustice, hardship or even deviation from established law, or usage, reap the utmost profit that such labour can be made to yield, consistently with regard due, […], to the health and permanent welfare of the individual, and that, from the period, whatever it may be, of his being taken under public care, until the expiration of his minority (Bentham, 1796, p. 53).”

So, what happens to the most common case of labour, number 4, that of extra-ordinary ability to labour? If a person with no limbs can be forced to labour for his relief, what then for those who are unemployed but with no physical or mental problems, but simply bad luck, a change in the economic situation, the introduction of machinery leading to unemployment or any other normal misfortune that can befall a worker? Again, the answer is obvious, you either earn your relief in the workhouses (or as Bentham terms them Houses of Industry) or you get no relief. So Bentham argues for the creation of these Houses of Industry by the government (as public money is needed to ensure continuity).

However, this leads to an obvious question, if we are going to build Houses of Industry and are going to force people to work to obtain relief (e.g., a more modern argument is found in work-fare or the recent suggestion that kids volunteer to get into the labour market to keep benefits), why do we not just create government industries and jobs and pay these workers at the social subsistence wage, why do we need to offer “relief” and pay below the socially accepted level of wages?

So, if we can create work in a work-house (whose products are then sold in the market), why not create real employment? Bentham’s argument seems to forget that in an economy with large agricultural production which was the case in 1797, there was such a thing as seasonal unemployment and that those who are in need temporarily will have work available later in the year; wouldn’t an advocacy of better wages and differing forms of payment actually be of more use? In other words, why not keep the amendment to the Poor Laws?

Moving forward a few years to when the capitalist system was completely consolidated (and if I dare say it today), given that unemployment is almost a constant condition of the capitalist economic system at least for most people for some period of time and for many people for long periods of time, the amount that would need to be invested to create workhouses may be better spent to cover those in temporary need, provide work at the normal wage levels in a situation of economic crisis, and ensure the survival of those who simply are unable to find employment?

From his discussion on poverty and indigence, it is evident that Bentham was strongly opposed to the poor law reform of 1795-7. He launched his attack in a pamphlet in 1797 called “Observations on the Poor Law Bill introduced by the Right Hon. William Pitt”:

Bentham has three general interconnected criticisms of the 1795-7 Poor Law Reform. First, he opposes the Bill because he believes that it tacitly assumes that all poor people are qualified for relief unless it is proven otherwise.

He wants the Bill to clearly state who is eligible for relief.

He never denies the right of those unable to work or those who must remain unemployed for part of the year to obtain relief, these constitute his deserving poor.

However, there are those who are indolent, dissolute, etc. and they are not entitled to have the same things as their more industrious or unfortunate brethren.

Bentham believes that people have to demonstrate that they deserve relief. This criticism concerns the different notions of entitlement versus eligibility found in the natural rights theories versus utilitarianism respectively (See e.g., Bentham 1797, p. 37).

The second criticism relates to his theory of wages which derives from his philosophical writings. He argues that the bill treats everyone equally, as everyone is entitled to the same benefit. As such, there will be equal rewards for industriousness and indolence, which is inconsistent with the principles of utilitarianism (See e.g., Bentham, 1797, p. 27). Bentham’s argument on wages reflecting productivity influences the new economic theory that was developed in 1870 to replace the classical theory.

Third, he argues that the poor law reform is an attack on income (guaranteeing all workers the same income), capital (cow-money clause) and hence on property (which people have because they were industrious and frugal).

In addition, to the other criticism of the Cow money clause, Bentham argues that this could be a bribe for votes for those who could actually vote (Bentham, 1797, p. 18). He does make a good point in this section; he states that this clause is inconsistent with the on-going enclosures of the commons. Either the ownership of land is good for the workers (which this bill implies) or not (as implied by the Enclosure Acts), it cannot be both (Bentham, 1797, p. 21).

Bentham appears to believe that, by nature, people are generally indolent, and hence not entitled to charity, because immoral behaviour should not be rewarded.

The perspective embodied in the 1795-7 reform included disqualification for relief (or charity) upon refusal of employment, in other words, all were assumed entitled to relief unless they demonstrated that they were not, that is they refused to work to earn their subsistence.

This position appears in the theory and in the bill. Bentham believes that people are not entitled, until they demonstrate that they are eligible for relief. This distinction between deserving and undeserving poor is then embodied in the writings of the wages-fund authors in their criticisms of the poor law.

In this case, we see Bentham arguing that poverty is both natural and moral.

The Poor – Moral Failures?

Some people (the undeserving poor) are poor because they are indolent, negligent and dissolute and they should not be treated in the same manner as the deserving poor (Bentham, 1797, p. 7).

The first two criticisms are embodied in the following:

Besides the general danger (the danger of idleness) inseparable from the home-provision system, aparticular source of danger seems to be opened up by the wording of this clause [supplemental-wage clause].

By his character for negligence or idleness, a man though in respect of bodily ability not unequal, perhaps to the fullest rate of earnings, shall have so ordered matter that no master will employ him but at a rate more or less inferior to that rate. […] for, whatever may have been the original cause of the inability, the existence of it is not the less real.

So far, then, as this cause of inability extends, that is so far as the class of the idle and negligent, and the dissolute extends […] the effect of it seems to be the putting the idle and negligent exactly upon a footing in point of prosperity and reward with the diligent and industrious (Bentham, 1797, p.7, original italics).

His final criticism that it is a threat to income, and capital appears in the discussion of the “Cow-Money Clause” (Bentham, 1797, pp. 16-21).

The threat of the Poor Laws to property appears in his discussion of the “Relief Extension Clause” (Bentham, 1797, p. 25). In both cases, the poor law is seen as threatening these specific forms of property, by making them available to those that do not deserve them since they are not earned through their hard work.

In light of his criticisms, what are Bentham’s suggestions for dealing with poverty?

His suggestions are threefold:

First, that relief be provided by private charities, not the government.

Second, some mechanism to discern deserving poor from lazy, indolent people must be devised to ascertain eligibility for relief (this he has done extensively, some of which we discussed above).

Third, he suggests that the temporary poor (those who are industrious, but have for a short-time fallen on hard-times out of misfortune) should obtain loans (if, of course, there is a possibility of repayment) rather than obtain relief.

The first two suggestions should sound familiar to all those that are following the debate on welfare reform today in the UK.

In some senses, the third suggestion can be found in the expensive but easy credit provided to the poor and working class; welcome to debt to add to your misery.

Malthus:

“As a previous step even to any considerable alteration in the present system, which would contract or stop the increase of the relief to be given, it appears to me that we are bound in justice and honour formally to disclaim the right of the poor to support (Malthus, 1798, p. 201, original italics).”

Malthus

In many senses, Malthus is so extreme that he is a bit out of fashion in mainstream discussions. Periodically, a statement by modern politicians hints of a strong Malthusian bias. We hear this when they talk about the poor having large families which are costing us so much money to support.

In fact, many arguments on the part of the extreme right have a strong Malthusian stench (including his opposition to birth control and abortion). Given Malthus’s Principle of Population, there is only one way to consider poverty and its elimination. His argument provided one leg of the attack on the classical economic theory of subsistence wage and the shift away from the notion that the economic system is responsible for the creation of poverty.

For the most part, Malthus insisted that poverty is a natural phenomenon arising from the difficulty in procuring the subsistence of the working class. This difficulty, deriving in his later works, from the theory of differential rent, places the burden for control on the poor. In other words, the problem caused by natural phenomenon can only be alleviated through acting on another natural phenomenon, i.e., the supply of labour.

Given Malthus’s prohibition on moral grounds of the use of contraceptives prior to marriage, the only solution to limit the labour supply (so that it is commensurate with the growth of subsistence) can be found in abstinence prior to marriage on the part of the working class or in delayed marriages until the workers could afford to have a family (Malthus, 1798, pp. 169-73).

In Malthus, poverty derives from natural laws governing population growth and agricultural production and it cannot be overcome by changes in institutions and/or human laws. Malthus uses this argument as a criticism against the Poor Laws and against the egalitarian ideas of reformers who were trying to improve the conditions of the working class in Britain.

According to Malthus, attempts to abolish or diminish the inequality in the distribution of wealth and income would only reduce everyone to the same level of poverty because the growth of population could not be checked except by resort to contraceptives and abortion (which he considered to be vices, he was a reverend) or through starvation and misery. How often have we heard this line from politicians?

Malthus argued that the pressure of population on scarce resources is the cause of poverty, and that this rules out any possible improvement of the living conditions of the working classes. The only way in which wages can permanently increase is if population growth is to be checked. In that situation and in that situation only, where the growth of the labouring population is checked in some manner could the working class benefit from the increase in capital accumulation.

Malthus directly addresses the Poor Laws in the Essay on Population. He argues that there had been a massive increase in the number of paupers and in the poor rates, and that this is “inconceivable” in such a flourishing nation.

He states that irrespective of how much people may want to remove the poor laws, they are so deeply embedded in the society and the relief they give so widely extended, that “no man of humanity could venture to propose their immediate abolition” (Malthus, 1798, p. 200).

Instead, he argues that attempts should be made to mitigate their effects and to stop their future increase and suggests a gradual abolition. The Poor Laws create “tyranny, dependence, indolence, and unhappiness” (Malthus, 1798, p. 201). He states that the first thing to do is to deny the right of the poor to relief.

The next step is to pass a law preventing both legitimate and illegitimate children from obtaining relief from the parish (Malthus, 1798, pp. 201-2).

According to Malthus, this law will not stop marriages of workers from happening, but it will make them and their offspring “immoral” (Malthus, 1798, p. 202). Unlike what we see in the later wages-fund authors (Nassau Senior and JR McCulloch), where they maintain that these people must be punished, Malthus holds that punishment is directly provided by the laws of nature (society’s laws have a much weaker effect).

According to Malthus, the punishment of nature is poverty. Given that there would be no poor relief, they would have to rely upon private charity.

[…] He should be taught to know that the laws of nature, which are the laws of God, had doomed him and his family to suffer for disobeying their repeated admonitions; that he had no claim ofright on society for the smallest portion of food, beyond that which his labour would fairly purchase; and that if he and his family were saved from feeling the natural consequences of his imprudence he would owe it to the pity of some kind benefactor, to whom, therefore, he ought to be bound by the strongest ties of gratitude (Malthus, 1798, p. 202).

Malthus recognizes that the implementation of his suggestion would result in severe hardship, as there is no reason for an increase in private charity.

Moreover, he insists that increases in private charity must be prevented at all costs or this will defeat the purpose of eliminating the poor laws. If his suggestion is followed, he believes that this will reduce the poor rates and they would be extinguished (probably along with the poor).

Finally, he argues that the poor laws have tended to “counteract the natural and acquired advantages of this country” (Malthus, 1798, p. 207). By this he means that the poor laws have diminished the resources of a country by pulling them away from economic growth to maintain the working class. Their continuance can only make the situation worse, by reducing everyone to the same level.

Some more history:

The ideological attack on the 1795-7 Poor Law reform enabled the roll-back of the reform.

The Poor Law reform of 1819 was based upon 3 bills that were introduced by Sturges Bourne (Tory) in 1818.

The Poor Law Amendment Bill attempted to abolish the allowance system (i.e., higher relief for larger families) by removing children from parents unable to support them. Needless to say this was pretty controversial even in the 19th century. They were then to be placed in schools or workhouses (i.e., find them a trade or put them to work).

Magistrates were given the right to adjudicate on the amount of relief and eligibility for relief based upon ‘the character and habits’ of the recipients (Cowherd, 1977, p. 72). Two other parts allowing for the removal of Scots and Irish were introduced (obviously the labour shortage in the cities was reduced) and putting those paying the poor rates on a parish Vestry to adjudicate those eligible were passed.

The Old Poor Law was overturned by the New Poor Law (1834).

The Old Poor Law was overturned by the New Poor Law (1834).

Just like today’s reform, it was upon the theories and conjectures rather than upon the reports of the commission’s investigators, that the Poor Law Commission wrote its report and based its recommendations.

Cowherd shows that information which derived from the investigations which ran contrary to the opinions of political economists were ignored or discredited by the heads of the Poor Law Commission, Edwin Chadwick and Nassau Senior (yes, the man above). In fact, the members of the commissions were so preoccupied with the doctrines espoused by political economists, that they did not take into account seasonal unemployment.

The Poor Law Amendment Act (1834) removed control of the administration of the Poor Law from the parishes and placed it under control of a central body of Commissioners. It eliminated the role of poor relief to supplement wages, outdoor relief to able-bodied people, and set the criteria for relief upon the principles of “deterrence and less eligibility.”

The principle of “less-eligibility” as articulated by Jeremy Bentham was that the situation in the work-houses would be worse than the worst possible conditions of employment of the working class outside of the work-houses. (poster from 1837 of new poor law)

This conception provided for the separation of families, that is, husbands, wives and children would be separated upon entering a work-house. Furthermore, the changes enacted by Pitt in reference to the Laws of Settlement and Bastardy were repealed, which induced additional hardships on the workers.

A large influx of Irish and Scottish migrants to England (that were desperately needed earlier in the manufacturing sector especially in cotton textile manufacture) who were eligible for relief under the relaxed Laws of Settlement of 1797 was considered problematic. So, in an attempt to stem what they believed to be an increasing tendency for relief expenditures, the Poor Law Commission argued that the only grounds for settlement would be birth.

This put the situation back to that articulated in the 1622 Settlement Act.

Further, given their view that poverty existed because of redundant population, they argued that in order to deter the existence of the redundant population, the mother of an illegitimate child should become solely responsible for its welfare, and the law then denied relief to the child. This system lasted until it was finally replaced by the social welfare state.

Further, given their view that poverty existed because of redundant population, they argued that in order to deter the existence of the redundant population, the mother of an illegitimate child should become solely responsible for its welfare, and the law then denied relief to the child. This system lasted until it was finally replaced by the social welfare state.

So how does all this history and theory relate to the modern discussion?

A lot of it is obvious.

The attack on people on disability where they are being tested to determine whether they are “deserving” or “undeserving” poor comes straight out of Bentham’s criteria.

Protesters Occupying Nottingham’s Atos Assessment Centre Confronted by Police

In fact, the medical tests being administered by ATOS to determine if you actually are sufficiently disabled are exactly that … their purpose is to get as many people off of incapacity benefit and income support and onto employment and support allowance (ESA) as possible (moving people from £91/week to £65.45 if found completely able to work; there is an intermediate phase for those found able to do some work).

For those lazy long term unemployed people (undeserving poor), benefits are being slashed and limited; we are looking at the relocation of people as their housing benefits will no longer cover the rent. The idea that people are lazy and will work only when forced to do so, again comes right from Bentham; it is the old punishment/pleasure argument.

The whole idea of a benefit cap is based upon the principle of lesser eligibility devised by Bentham. The fact that people actually buy into this idea irrespective of the size of families and location where people live is rather telling; they have been able to create a divide and rule argument that resonates with employed people, splitting those working from those unable to find work.

Just as in the case of the 19th century workhouses, the jobs do not exist. Obviously, if these jobs did exist, businesses would be hiring people. Moreover, if these jobs did exist, certainly the unemployed would have been happily working in them as opposed to working in horrific conditions in a workhouse. So the punishment of the poor did not create jobs.

Be NOT afraid!

On the issue of forcing people to work a la Bentham, Iain Duncan Smith has raised the possibility of forcing those on benefit to volunteer as the first step into work;[xix] he even went so far as to say that they should be forced to do 4 weeks of unpaid labour or lose their benefits:

“The Department for Work and Pensions plans to contract private providers to organise the placements with charities, voluntary organisations and companies. An insider close to the discussions said: “We know there are still some jobseekers who need an extra push to get them into the mindset of being in the working environment and an opportunity to experience that environment. This is all about getting them back into a working routine which, in turn, makes them a much more appealing prospect for an employer looking to fill a vacancy, and more confident when they enter the workplace. The goal is to break into the habit of worklessness.[xx]”

Quite simply, is this a way to get people back to work or to provide free unpaid labour for business? I honestly think it is the latter and the problem with this is that this discentivises (to use his word) businesses to create paid jobs when they can simply hire people to do unpaid labour. How wonderful to have forced labour to exploit where they do not have to pay them!

Duncan Smith is trying to create a similar situation as that of the workhouses without the workhouse itself. If you cannot survive on benefits as they have been so seriously reduced; then work becomes attractive just as given the conditions in a workhouse, you would even be better off begging than to enter them.

However, the same problem arises. If the jobs do not exist, how can you possibly work? There is a serious lack of reality going on here. What you are essentially doing is impoverishing the poor and the disabled.

Even in the context of bourgeois economic theory, impoverishing the poor means a decrease in effective demand; effective demand is the engine of growth and job creation in most of the advanced capitalist world.

This is simply nonsensical and based upon fantasy rather than the reality even acknowledged by mainstream economics.

Why not advocate direct government jobs creation?

This may not have been obvious in Bentham’s time, but it is rather obvious and relevant today. Certainly, these jobs are not materialising, this is evident if one looks at the employment statistics.

We are at the highest level of unemployment (2.62 million people, at 8.3%) since 1994 and 1996 respectively; youth unemployment (16-24 years) is the highest it has been in history at 21.9%. Rather than relying on a private sector which is both unwilling and unable (following their own criteria for employment decisions) to create jobs, why does the government not create jobs rather than pushing policies that will are estimated to lead to 710,000 jobs being shed in the public sector.[xxi] In a period of severe economic problems, why shed jobs and cut benefits instead of creating jobs and increasing incomes of the poor?

Given the situation and the orientation of this government, quite honestly (and I know I have been saying this for a while) I am expecting them to open privately owned and operated workhouses where the poor are forced to labour at below minimum wages.

They are almost there; their advocacy of forced volunteerism is a first step. But we know from history that this did not work back in the 19th century and that is why it was abandoned in the 20th century. But, of course, the abandonment of the punishment of the poor for the failures of the system was not done voluntarily in 1795-7 or in the 1940s:

A Million for The Alternative March 26th 2011

It required a strong movement of working people and the unemployed; it required spontaneous action (rioting and direct action), strikes by unionised workers and the threat of a powerful left alternative.

These changes were done to save the system, not done because those running the government and the economy were people that gave a damn about the poor and the working class; it was not about paternalism, merely self-interest.

It looks like we are once again heading for a 21st century revival of failed policies to fight poverty; the problem of poverty and unemployment has never been a question of choices or immorality; it comes commensurate with a capitalist economic system that is based upon production for profits, where economic decisions are based on current and potential profitability rather than upon the needs of all citizens.

We know why wealth and income inequality exists and it has nothing to do with morality of the poor and everything to do with the failures of the system and the immorality of those in government.

We know why wealth and income inequality exists and it has nothing to do with morality of the poor and everything to do with the failures of the system and the immorality of those in government.

If we really want to do something to ensure the rights of the poor and disabled, it is the capitalist system and the ideology that sustains it that must end. Move to a different criterion which ensures that those do what they can and ensures that all people are covered:

From each: According to their abilities; To Each: According to their Needs

Primary References:

Bentham, Jeremy, Writings on the Poor Laws, volume I, edited by Michael Quinn, Clarendon Press Oxford, 2001.

Bentham, Jeremy, (1796) “Essays on the Subject of the Poor Laws, Essay I and II,” in Writings on the Poor Laws, Volume I, pp. 3-65.

Bentham, Jeremy (2/1797) “Observations on the Poor Law Bill introduced by the Right Hon. William Pitt,” unpublished manuscript appearing in Observations on the Poor Bill, introduced by the Right Honourable William Pitt, (Joseph) Hume Tracts Number 38, University College London, pp. 2-48.

Cowherd, Raymond (1977) Political Economists and the English Poor Laws: A Historical Study of the Influence of Classical Economics on the Formation of Social Welfare Policy, Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press.

Malthus, T.R. (1803) An Essay on the Principle of Population, seventh edition, London: J.M. Dent and Sons, 1973 (1872).

Mill, James (1826) Elements of Political Economy, Third Edition, New York: A.M. Kelley Publishers, 1963.

Pitt, William (1806) The Speeches of the Right Honourable William Pitt in the House of Commons, in Four Volumes, London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, and Orme.

Senior, Nassau, W. (1831) Three Lectures on the Rate on Wages, Second Edition, New York: A.M. Kelley Publishers, 1966.

________________________________________

[i] http://www.stormfax.com/1dickens.htm

[ii] http://www.rightsnet.org.uk/forums/viewthread/2496/

[iii] https://blacktrianglecampaign.org/2011/08/28/andy-worthingtons-blog-brutal-benefit-cuts-for-the-disabled-are-leading-to-suicides-in-the-uk/; http://www.dpac.uk.net/2011/05/debbie-jolly-the-billion-pound-welfare-reform-fraud-fit-for-work/

[iv] http://www.guardian.co.uk/society/2012/feb/05/benefit-cuts-fuelling-abuse-disabled-people

[v] http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-politics-12486158

[vii] http://www.dwp.gov.uk/docs/eia-benefit-cap-wr2011.pdf, p. 2, my emphasis.

[ix] http://www.dwp.gov.uk/docs/eia-benefit-cap-wr2011.pdf, p. 5

[x] http://www.dwp.gov.uk/docs/eia-benefit-cap-wr2011.pdf, p 4.

[xi] http://www.dwp.gov.uk/docs/eia-benefit-cap-wr2011.pdf, p. 8.

[xii] http://www.dwp.gov.uk/docs/eia-benefit-cap-wr2011.pdf, p. 7.

[xiii] See the Guardian blog on the debate in the Lords on welfare reform:

http://www.guardian.co.uk/society/blog/2012/feb/01/welfare-benefits;

http://www.guardian.co.uk/politics/2012/jan/25/welfare-bill-defeated-lords?INTCMP=SRCH;

and

http://www.guardian.co.uk/society/blog/2012/jan/17/disability-welfare

[xv] http://www.guardian.co.uk/society/blog/2012/feb/01/welfare-benefits

[xvi] In 1939, numbers of people residing in workhouses were 100,000; see: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Workhouse.

[xvii] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1948_National_Assistance_Act

[xviii] This was known as the Speenhamland System, see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Speenhamland_system.

[xix] See for example: http://www.metro.co.uk/news/854793-jobless-urged-to-work-for-free

[xx] http://www.guardian.co.uk/politics/2010/nov/07/unemployed-unpaid-work-lose-benefits

[xxi] This was described in greater detail in, http://socialistresistance.org/2912/what-camerons-lost-decade-means-for-us

3 Responses

I can only agree with everything that has been said. The disabled people’s only crime to to be born without full abilities (mental or physical) in a society that has let itself be ‘brainwashed’ into thinking they are all fiddling the system. The media has become a tool of the establishment to convince the “normal” masses we all are hypochondriacs who are in danger of being needy!

We Need a Better Government and Constitutional Protection for the

Welfare of the Poor and Vulnerable Now

Scrap MP’S Expenses and Warmongering in Afghanistan Not Welfare

We Need Humanity Not Bone Headed Politicians Inflicting Misery