Benefits claimants are subjected to an ‘amateurish, secret penal system which is more severe than the mainstream judicial system’, writes Dr David Webster of the University of Glasgow.

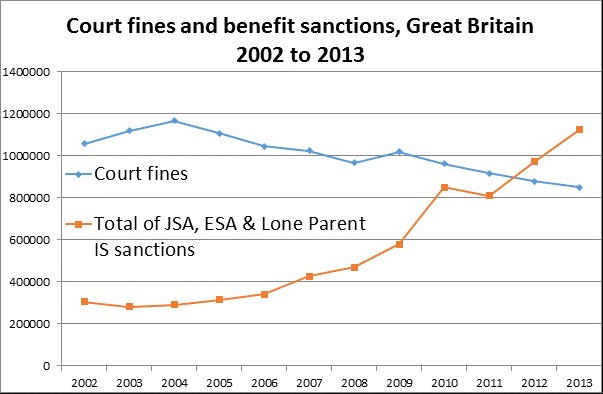

Few people know that the number of financial penalties (‘sanctions’) imposed on benefit claimants by the Department of Work and Pensions now exceeds the number of fines imposed by the courts. In Great Britain in 2013, there were 1,046,398 sanctions on Jobseeker’s Allowance claimants, 32,128 on Employment and Support Allowance claimants, and approximately 44,000 on lone parent recipients of Income Support.

Few people know that the number of financial penalties (‘sanctions’) imposed on benefit claimants by the Department of Work and Pensions now exceeds the number of fines imposed by the courts. In Great Britain in 2013, there were 1,046,398 sanctions on Jobseeker’s Allowance claimants, 32,128 on Employment and Support Allowance claimants, and approximately 44,000 on lone parent recipients of Income Support.

By contrast, Magistrates’ and Sheriff courts imposed a total of only 849,000 fines.

Sanctioned benefit claimants are treated much worse than those fined in the courts.

The scale of penalties is more severe (£286.80 – £11,185.20 compared to £200 – £10,000).

Most sanctions are applied to poor people and involve total loss of benefit income.

Although there is a system of discretionary ‘hardship payments’, claimants are often reduced to hunger and destitution by the ban on application for the first two weeks and by lack of information about the payments and the complexity of the application process.

The hardship payment system itself is designed to clean people out of resources; all savings or other sources of assistance must be used up before help is given.

Decisions on guilt are made in secret by officials who have no independent responsibility to act lawfully; since the Social Security Act 1998 they have been mere agents of the Secretary of State.

These officials are currently subject to constant management pressure to maximise penalties, and as in any secret system there is a lot of error, misconduct, dishonesty and abuse.

The claimant is not present when the decision on guilt is made and is not legally represented.

While offenders processed in the court system cannot be punished before a hearing, and if fined are given time to pay, the claimant’s punishment is applied immediately.

Unlike a magistrate or sheriff, the official deciding the case does not vary the penalty in the light of its likely impact on them or their family.

If the claimant gets a hearing (and even before the new system of ‘Mandatory Reconsideration’ only 3 per cent of sanctioned claimants were doing so), then it is months later, when the damage has been done.

‘Mandatory reconsideration’, introduced in October 2013, denies access to an independent Tribunal until the claimant has been rung up at home twice and forced to discuss their case with a DWP official in the absence of any adviser – a system which is open to abuse and has caused a collapse in cases going to Tribunal.

Yet the ‘transgressions’ (DWP’s own word) which are punished by this system are almost exclusively very minor matters, such as missing a single interview with a Jobcentre or Work Programme contractor, or not making quite as many token job applications as the Jobcentre adviser demands.

How did we get to this situation?

Until the later 1980s, the social security system saw very little use of anything that could be called a sanction.

Unemployment benefits were seen as part of an insurance scheme, with insurance-style conditions.

Any decision on ‘disqualification’ (as it was called) from unemployment benefit was made by an independent Adjudication Service, with unrestricted right of appeal to an independent Tribunal.

The maximum disqualification was 6 weeks, and those disqualified had a right to a reduced rate of Supplementary Benefit assessed on the normal rules.

‘Sanctions’ are almost entirely a development of the last 25 years.

The British political class has come to believe that benefit claimants must be punished to make them look for work in ways the state thinks are a good idea.

Yet the evidence to justify this does not exist.

A handful of academic papers, mostly from overseas regimes with milder sanctions, suggest that sanctions may produce small positive effects on employment.

But other research shows that their main effect is to drive people off benefits but not into work, and that where they do raise employment, they push people into low quality, unsustainable jobs.

This research, and a torrent of evidence from Britain’s voluntary sector, also shows a wide range of adverse effects.

Sanctions undermine physical and mental health, cause hardship for family and friends, damage relationships, create homelessness and drive people to Food Banks and payday lenders, and to crime.

They also often make it harder to look for work.

Taking these negatives into account, they cannot be justified.

Benefit sanctions are an amateurish, secret penal system which is more severe than the mainstream judicial system, but lacks its safeguards.

It is time for everyone concerned for the rights of the citizen to demand their abolition

Update Friday 23rd October 2015:

Dr. David Webster writes . . .

Dear Colleague

The government’s response to the House of Commons Work & Pensions Committee report on ‘Benefit Sanctions Policy beyond the Oakley Review’ was published yesterday, 22 October.

The response itself, together with an accompanying letter from Iain Duncan Smith to the Committee chair, is at:

The accompanying Parliamentary statement by Iain Duncan Smith is at:

Reaction by the Committee chair Frank Field is at:

I will be circulating a detailed analysis of the response in the next week or so.

Meanwhile, here are the key points about what will and will not change about the sanctions regime as a result of the response:

* The government is continuing to refuse the broad independent review of sanctions which the Committee and others have repeatedly called for.

* Its response (pp.2-3) also deliberately evades the Committee’s specific call for review of the effectiveness of the lengthening of sanctions introduced in 2012.

* The government claims that it will trial a ‘system of warning’ before a sanction is imposed.

However the Committee (and Oakley in July 2014) called for a first ‘failure’ to lead to a warning letter, and only a second or subsequent failure to result in a sanction.

What the government is proposing is different.

It is simply a delay of 14 days in imposing a sanction, during which the claimant will be able to make representations.

* The government has admitted at:

. . . that 47,239 JSA claimants (6.9%) who were sanctioned in 2014 did not receive notification before the money failed to appear in their account.

Applying this percentage to the whole period of the Coalition government, there will have been about 279,000 cases where claimants had their benefit stopped before being notified.

This issue was highlighted by Oakley in July 2014.

The government now proposes to deal with this by reintroducing computer-generated notification, but admits that this will be unlikely to be 100% successful.

* The current provision that sanctioned claimants, other than arbitrarily-defined ‘vulnerable’, cannot apply for hardship payments for the first two weeks of a sanction is responsible for destitution and food bank use on a large scale.

The Committee firmly recommended that all sanctioned claimants should be able to apply from day one.

The government has now agreed only to consider extending the definition of ‘vulnerability’ for the purposes of day one application to ‘a wider group of claimants’.

Duncan Smith’s parliamentary statement, but not the response itself, specifically mentions people with mental health conditions and the homeless.

The government says it has also speeded up the hardship claim process so that awards are paid within 3 days, and that subject to feasibility the decision maker will in future set up an appointment to discuss hardship payments where claimants are ‘vulnerable’ or have children.

* The government has flatly refused the Committee’s recommendation to track what happens to claimants in terms of employment and claimant status after a sanction, in spite of clearly having the capability to do so.

* The government appears to have given up any attempt to ensure that the one third of all sanctioned claimants whose alleged ‘failure’ is not actively seeking work do not wrongly lose housing benefit as a result.

These claimants are ‘disentitled’ as well as ‘sanctioned’ and the response (p.5) accepts that Housing Benefit (HB) may be affected as a result.

A recent clarificatory circular to local authorities, HB Bulletin U1-2015 (30 Sep 2015) related only to the two thirds of penalties which are purely ‘sanctions’ and not ‘disentitlements’.

Dr David Webster

Honorary Senior Research Fellow

Urban Studies

School of Social and Political Sciences

University of Glasgow

Email: david.webster@glasgow.ac.uk