![]()

‘Only a crisis – actual or perceived – produces real change,” wrote Milton Friedman. I know, I don’t like him either, but apparently not liking him doesn’t make him go away. “When that crisis occurs, the actions that are taken depend on the ideas that are lying around.”

Having had no shortage of crises these past two years, we’ve had the opportunity to test this theory: and sure enough, the coalition – for which read a Tory on a motorbike, with a sidecar full of petrified Lib Dems – has seen its ideas flourish into radical action. There’s no caretaker atmosphere in this government, no case-by-case appraisal of what a sensible path might be. Everything from the dismantling of the NHS to the careful desecration of the principles of social security has proceeded according to ideas they had lying around. It would have been helpful if we’d known about them upfront, but there’s no use crying over specious manifestos.

These ideas have turned into something like a catechism, expressed from many mouths in almost identical words. First, the Labour government got us into this mess; second, they got us here with their excessive spending on welfare; third, if we don’t tackle that welfare spend, we’ll end up like Greece.

If you were to strip this narrative down to a single belief, it would be that, as a society, we were pooling too many of our resources and spending them too generously on one another, and that was neutering our economy.

The counter-argument to all this has, so far, been: part head-slapping disbelief (how could a global meltdown be Gordon Brown’s fault?); part leftie outrage (are we seriously going to look at the excesses of the noughties and blame the long-term unemployed and the disabled?); and part smartarse Keynesianism (we’re nowhere near ending up like Greece – but if that’s where we wanted to end up, then paring back public spending, cutting jobs, demolishing tax receipts, increasing the welfare bill, castigating welfare recipients and destroying consumer confidence would be a really good place to start).

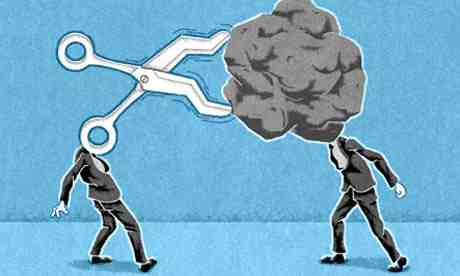

The problem with all these arguments is not that they’re wrong, but that they lack co-ordination and arrive too late. The idea of political discourse as a process of sustained argumentation – in which an idea is advanced, examined and accepted, or refuted – is utopian. Modern politics is about creating a narrative and making it stick. It doesn’t matter if some of its details are hurried or sloppy or openly untrue; if it has enough internal consistency and the repetition of any given part gives the impression of having corroborated the whole, that’ll do.

Don’t be downhearted, however: there’s no shortage of crises on the horizon, so there is plenty of scope and urgent reason to build the new ideas to have lying around when these crises arrive. At a wild guess, the next political upheaval will occur when everybody realises how much poorer they are, directly or indirectly because of austerity.

It sounds so wholesome and bracing in the abstract, this word – all the fun of the second world war, none of the death. I bet it won’t feel very bracing in real life: the working family tax credit cuts are yet to be felt; unemployment won’t peak until the end of this year, and will continue at that level for another 12 months; public sector job losses haven’t yet finished; and regional pay freezes and caps on housing and universal benefit have yet to kick in.

These are just the changes slated in the current spending review. The director of the Institute for Public Policy Research, Nick Pearce, wrote some predictions of the spending review for 2013, which take into account unexpectedly weak growth and the Office for Budget Responsibility’s downward forecasts for the near future. Pearce predicts that departmental spending “will be cut by an annual average of 3.8% in real terms in 2015/16–2016/17. This is even bigger than the 2.3% average annual real cut that departments have been given in the current spending review period.” If there simply isn’t the fat left to trim, the savings will have to be found from welfare – which, assuming pensioners remain the Cinderellas of the benefit-scrounging story (innocent, selfless, small feet), leaves the government trying to find yet more savings from tax credits, housing benefit and support for people with disabilities.

This is a prediction and not an actuality, but its key usefulness is in underlining that the left has to be ready. The current oppositional mood seems to be defined by the fear of replaying the early 90s, mingled with a sense that, even if the crash wasn’t Labour’s fault, some formless act of public atonement needs to be seen. Labour’s storyline is, as a consequence, lukewarm – it neither accepts nor consistently rejects responsibility for the deficit; it doesn’t agree with austerity but has no enthusiasm for government spending; it might feel bad for disabled people in penury, but doesn’t make a coherent case against the absurdity of trying to claw back this nation’s prosperity from its poorest.

Twitter: @zoesqwilliams

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.