Lord Hutton has proposed some worthwhile, though pretty limp wristed, pension reforms, yet the problem with Britain’s ever more dysfunctional pensions system is not so much that public sector pensions are too generous, but the almost criminal damage that has been inflicted by successive governments on private pensions.

I say successive governments, yet the chief culprit is a familiar one – our old friend Gordon Brown, who by abolishing the tax credit on dividends to fund whatever nonsense the public sector priority of the time might have been, set in train the now almost total destruction of privately provided defined benefit pensions, and severely undermined the merits of pensions saving all round. The eminence grise of this policy is now the shadow Chancellor, Ed Balls. No wonder he’s not had much to say amid the storm of Labour protest over Hutton’s recommendations.

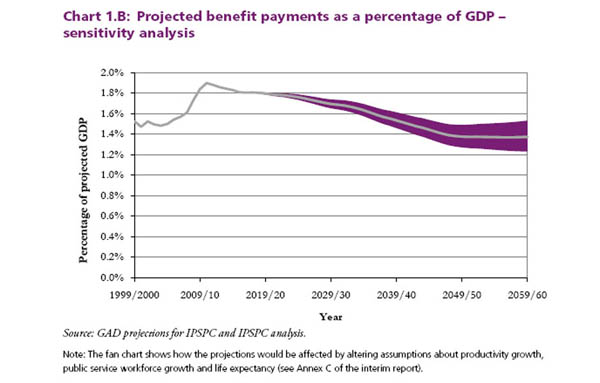

As it happens, the chief justification for public sector pension reform – that public pensions are becoming progressively more unaffordable – is something of a myth, as the detail of Lord Hutton’s report makes abundantly clear. Take a look at the following graph, which you can click to englarge.

What it shows is that even without the Hutton reforms, the cost of public sector pensions on the key measure of affordability (as a percentage of GDP) has already peaked and is set to decline markedly over the years ahead. That’s because public sector pensions have already been quite significantly reformed, the two main changes being higher employee contributions and the shift from RPI to the generally lower CPI for indexing purposes.

Office for Budget Responsibility projections, as shown in the bar chart beneath, show much the same thing. Far from rising as a proportion of GDP, the cost of public sector pensions is set to decline even assuming no further reform.

Now even at 1.4pc of GDP – the projected cost by 2060 assuming no further reform – pension payments will still consume a humungous sum of money. At getting on for a twentieth of all public spending, it’s roughly equivalent to what’s spent on defence. But the point is that this is more a question of public spending priorities than affordability as such. If public sector pensions are affordable at close to 2pc of GDP (the current cost), then they are most certainly affordable at 1.4pc. This is not a demographic timebomb which if left unaddressed will completely sink the public finances.

There are plenty of reasons for wanting to address public sector pensions, but affordability is not really one of them. What are these reasons? The main one is perceived unfairness. As taxpayers, we all generally accept the case for contributing to universal education and healthcare, but most of us are going to have something of a problem with funding public sector pension benefits which have become far more generous than our own.

Pensions are at root only a deferred form of earnings. The problem is that taking into account these benefits, it is now more remunerative to work for the public sector than the private. This is obviously not just wrong in principle, but is also bad economics, for it crowds the wealth producing bit of the economy out and profoundly limits the scope for introducing private sector efficiencies into the provision of public services. In this sense, the present system of public sector pensions truly is unsustainable, for no economy where it is more attractive to work for the public sector than the private is going to remain competitive for very long.

I’m not going to try and argue that further public sector pension reform is unnecessary and wrong, but there is something plainly unsatisfactory about “race to the bottom” policy, or levelling public sector pensions down to the disgracefully low standards that rule in the private sector.

Having largely destroyed a perfectly good system of private sector pension provision, government now seems intent on doing the same to public pensions too. I exaggerate, of course, but only a little. Hutton could have gone the whole hog and as has occurred in Sweden, attempted to move public sector workers off defined benefit pensions altogether and onto the money purchase schemes that now rule in the private sector. But that would never have passed muster politically.

The bottom line is that far more has to be done to encourage adequate private sector saving for old age, including the reintroduction of the sort of tax breaks that Brown, and now his successors, have tended to target as an easy gain for the public finances. The chances of this happening are, regrettably, about zero.