By John Pring Disability News Service October 6th 2016

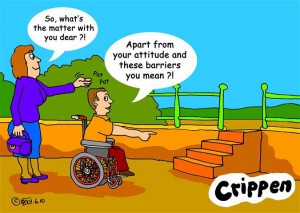

Disabled activists have highlighted the “shameful” access barriers they face on a daily basis, in a series of protests in Birmingham timed to coincide with the city hosting the Conservative party’s annual conference.

Members of Disabled People Against Cuts (DPAC) blocked buses, trams and other traffic, but also shamed city centre businesses for their lack of wheelchair access, as part of a day of action.

Their protests highlighted the UK’s continuing failure to comply with article 19 of the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, which covers disabled people’s right to live independently and be included in the community.

Bob Williams-Findlay, who helped organise the day of action on behalf of DPAC West Midlands, said disabled people had “played a Cinderella role” in society for too long and were still excluded from mainstream society, while changes that followed the introduction of the Disability Discrimination Act and the Equality Act had been “cosmetic”.

He said that austerity-driven cutbacks meant this was “only getting worse” and he and his fellow activists were “here to say that we are not putting up with it” and were “not prepared to carry on being Cinderella… we are here to demand that we go to the ball”.

The day of action focused first on a multi-million pound refurbishment of The Grand Hotel, an iconic Birmingham building, which includes a row of new, high-end, street-level businesses.

DPAC West Midlands pointed out that these businesses, including cocktail bar and restaurant The Alchemist, and a café, 200 Degrees, still had steps at their entrances, despite the millions of pounds spent on the refurbishment.

Although both businesses produced portable ramps to allow DPAC wheelchair-users to enter their premises, activists – who chanted “shame, shame, shame” and “let us in, let us in” – said this was not good enough after such expensive renovation work.

Their concerns were underlined when a portable ramp collapsed as one of the activists, Sam Brackenbury, was using it to leave The Alchemist.

Williams-Findlay, a former chair of the British Council of Disabled People, said Birmingham City Council was “shirking its responsibilities” under the Equality Act to ensure that such renovations ensured access for disabled people.

The group then moved to nearby Snow Hill railway station to protest at plans to remove more safety-trained guards from trains.

They pointed out that guards “play a crucial role in supporting disabled people to get on and off the train, by providing assistance and erecting ramps for wheelchair-users”.

Andy Thompson, one of the activists, said the threatened loss of guards was a “safety issue for the whole public and especially disabled people”, and he called on the government to “prioritise access and not spending on war and tax cuts”.

Protesters then blocked a main tram line through the city centre, and held up buses and other traffic, in protest at continued austerity cuts.

Police then escorted the disabled activists to a protest outside the party conference, near the International Convention Centre, before the day of action ended outside Birmingham City Council House, the headquarters of Birmingham City Council.

Sandra Daniels, from DPAC West Midlands, said the protest was about “the implications of not being able to work in a society geared up for those who can”, and the years of cuts to services, benefits and social care.

She said that access was “a basic right for people… even when shops have been refurbished, they are still not thinking about making sure disabled people can access them.

“They need to stop this slashing of disabled people’s services, their benefits, and stop excluding us and pushing us to the margins of society once again.

“Disabled people have fought for 40 years to be included in society and the Tories are trying to imprison us in our own homes and push us back; they want us out of view.”

Richard Norgrove, a surveyor with Hortons’ Estate, which is renovating The Grand Hotel, said there had been detailed discussions with Historic England, the city council and Access Birmingham over the refurbishment.

He said the building was listed II*, and posed a number of “constraints” that made including level access “difficult”.

He said he understood that steps at the front entrance suggested that the businesses did not welcome wheelchair-users.

But he said: “It is regarded as one of the most iconic buildings in Birmingham. We want access to all.

“It’s not as straightforward as it would seem to be. It’s quite a challenge to get level access. We don’t want to discriminate against anybody.”

But Tony Willis, chair of Access Birmingham, formerly known as the Access Committee for Birmingham, said the lack of steep-free access in Colmore Row was “ridiculous” and “cannot be right” when Hortons’ Estate had spent millions of pounds on the refurbishment.

He said: “We are very aware of what’s going on there and hoping that there will be a satisfactory conclusion.

“I’m a wheelchair-user and I’m not happy with steps.

“It seems that enforcement of the Equality Act is the burden of disabled people, and it shouldn’t be.

“It’s ridiculous. Why is it our burden? It is the law and there should be an enforcement agency that looks after the Equality Act.”

Richard Goulborn, the council’s head of planning management, said in a statement: “Birmingham City Council is committed to ensuring that the city’s buildings which are open to the public are as accessible as possible and under the Equality Act, the tenant, as service provider, is responsible for making arrangements to provide access to their premises – for example, having a demountable ramp and ensuring staff are trained to assist those with mobility issues when entering or leaving the premises.

“The Grand Hotel is a grade II*-listed building and the new shop fronts on the ground floor have been installed at the same level as the original shop fronts due to the level of the original floor structure inside.

“The internal floor structure prevents the floor levels being lowered inside the units and raising the level outside would mean significant works to replace the entire pavement, while installing permanent ramps could also create a potential hazard on the public footway.”

Meanwhile, an inquiry into disability and the built environment by the Commons women and equalities committee is accepting evidence from individuals and organisations until 12 October.

The committee “will explore the extent to which the needs of disabled people are considered and accommodated in our built environment, and ask whether more could be done to increase the accessibility and inclusivity of both new and existing properties and spaces”.